Key Points

-

Tumour cell dissemination is an early event in tumorigenesis and is relevant for metastatic progression (in particular for breast cancer). These data have led to the introduction of disseminating tumour cells (DTCs) in international tumour classification systems.

-

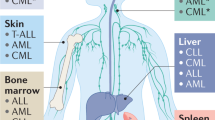

Bone marrow (BM) is a common homing organ for tumour cells that are derived from various types of epithelial tumours including breast, prostate and colon cancer. Tumour cells may either establish overt metastases in the BM, as is seen for patients with breast or prostate cancer, or re-circulate to other organs, such as liver or lung, where they find better growth conditions, as is evident in patients with colon cancer.

-

Significant technical advancements in immunological procedures and quantitative real-time PCR-based assays now allow DTCs to be identified and enumerated at frequencies of 1 per 106–107 nucleated blood or BM cells.

-

Sophisticated molecular techniques such as whole-genome analysis or gene expression profiling have been applied to obtain initial information on the molecular characteristics of DTCs. The current data indicate that most DTCs are dormant (non-proliferative) in situ. However, these cells are viable and can proliferate in cell culture in response to appropriate growth factors, such as the stem cell growth factors epidermal growth factor (EGF) and fibroblast growth factor 2 (FGF2).

-

DTCs can express cancer stem cell profiles (such as CD44+/CD24− in breast cancer patients) and exhibit stem cell properties such as resistance to chemotherapy and long-term persistence in the BM.

-

Identification of therapeutic targets on DTCs and circulating tumour cells (CTCs) and real-time monitoring of CTCs in cancer patients undergoing systemic therapy are the most important future clinical applications. In this context, the ERBB2 proto-oncogene has served as a proof-of-principle target for the monitoring and treatment of DTCs in human breast cancer.

Abstract

Most cancer deaths are caused by haematogenous metastatic spread and subsequent growth of tumour cells at distant organs. Disseminating tumour cells present in the peripheral blood and bone marrow can now be detected and characterized at the single-cell level. These cells are highly relevant to the study of the biology of early metastatic spread and provide a diagnostic source in patients with overt metastases. Here we review the evidence that disseminating tumour cells have a variety of uses for understanding tumour biology and improving cancer treatment.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

$209.00 per year

only $17.42 per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Boyle, P. & Ferlay, J. Cancer incidence and mortality in Europe, 2004. Ann. Oncol. 16, 481–488 (2005).

Eccles, S. A. & Welch, D. R. Metastasis: recent discoveries and novel treatment strategies. Lancet 369, 1742–1757 (2007).

Husemann, Y. et al. Systemic spread is an early step in breast cancer. Cancer Cell 13, 58–68 (2008). Here it was reported for the first time that tumour cells can disseminate systemically from earliest epithelial alterations in ERBB2 - and PyMT -transgenic mice and from ductal carcinoma in situ in women. A new hypothesis for cancer cell dissemination was proposed, which must be substantiated by further studies.

Pantel, K. & Alix-Panabieres, C. The clinical significance of circulating tumor cells. Nature Clin. Pract. Oncol. 4, 62–63 (2007).

Pantel, K. & Brakenhoff, R. H. Dissecting the metastatic cascade. Nature Rev. Cancer 4, 448–456 (2004).

Meng, S. et al. Circulating tumor cells in patients with breast cancer dormancy. Clin. Cancer Res. 10, 8152–8162 (2004).

Muller, V. et al. Circulating tumor cells in breast cancer: correlation to bone marrow micrometastases, heterogeneous response to systemic therapy and low proliferative activity. Clin. Cancer Res. 11, 3678–3685 (2005). This report demonstrates that CTCs are in a quiescent state (that is, are non-proliferating and Ki67-negative) and survive chemotherapy in a considerable fraction of treated patients with breast cancer.

Cristofanilli, M. & Mendelsohn, J. Circulating tumor cells in breast cancer: Advanced tools for “tailored” therapy? Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 17073–17074 (2006).

Uhr, J. W. Cancer diagnostics: one-stop shop. Nature 450, 1168–1169 (2007).

Paterlini-Brechot, P. & Benali, N. L. Circulating tumor cells (CTC) detection: clinical impact and future directions. Cancer Lett. 253, 180–204 (2007).

Fehm, T. et al. A concept for the standardized detection of disseminated tumor cells in bone marrow from patients with primary breast cancer and its clinical implementation. Cancer 107, 885–892 (2006). A recent concept for the standardization of DTC detection, describing in detail the confounding factors of immunocytochemical BM analyses and the recommended quality assurance procedures

Riethdorf, S. et al. Detection of circulating tumor cells in peripheral blood of patients with metastatic breast cancer: a validation study of the CellSearch system. Clin. Cancer Res. 13, 920–928 (2007).

Shaffer, D. R. et al. Circulating tumor cell analysis in patients with progressive castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 13, 2023–2029 (2007).

Kagan, M., Howard, D. & Bendele, T. in Tumor Markers: Physiology, Pathobiology, Technology and Clinical Applications. (eds Diamandis, E., Fritsche, H., Lilja, H., Chan, D. & Schwarz, M.) 495–498 (AACC Press, Washington, DC, 2002).

Cristofanilli, M. et al. Circulating tumor cells, disease progression, and survival in metastatic breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 351, 781–791 (2004). A pivotal clinical study that provided the first significant evidence for the clinical relevance of detecting CTCs in breast cancer patients with overt metastases.

Litvinov, S. V. et al. Expression of Ep-CAM in cervical squamous epithelia correlates with an increased proliferation and the disappearance of markers for terminal differentiation. Am. J. Pathol. 148, 865–875 (1996).

Smirnov, D. A. et al. Global gene expression profiling of circulating tumor cells. Cancer Res. 65, 4993–4997 (2005).

Hayes, D. F. et al. Circulating tumor cells at each follow-up time point during therapy of metastatic breast cancer patients predict progression-free and overall survival. Clin. Cancer Res. 12, 4218–4224 (2006).

Cohen, S. J. et al. Isolation and characterization of circulating tumor cells in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Clin. Colorectal Cancer 6, 125–132 (2006).

Moreno, J. G. et al. Circulating tumor cells predict survival in patients with metastatic prostate cancer. Urology 65, 713–718 (2005).

de Bono, J. S. et al. Potential applications for circulating tumor cells expressing the insulin-like growth factor-I receptor. Clin. Cancer Res. 13, 3611–3616 (2007). The reported data support the further evaluation of CTCs in pharmacodynamic studies and patient selection, particularly in advanced prostate cancer, exemplifying IGFR1 detection of CTCs under anti-IGFR1 therapy.

Danila, D. C. et al. Circulating tumor cell number and prognosis in progressive castration-resistant prostate cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 13, 7053–7058 (2007).

Nagrath, S. et al. Isolation of rare circulating tumour cells in cancer patients by microchip technology. Nature 450, 1235–1239 (2007). First report on a microfluidic platform ('CTC chip') that identified CTCs in the peripheral blood from 99% of patients with lung, prostate, pancreatic, breast or colon cancer.

Braun, S., Hepp, F., Sommer, H. L. & Pantel, K. Tumor-antigen heterogeneity of disseminated breast cancer cells: implications for immunotherapy of minimal residual disease. Int. J. Cancer 84, 1–5 (1999).

Thurm, H. et al. Rare expression of epithelial cell adhesion molecule on residual micrometastatic breast cancer cells after adjuvant chemotherapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 9, 2598–2604 (2003).

He, W., Wang, H., Hartmann, L. C., Cheng, J. X. & Low, P. S. In vivo quantitation of rare circulating tumor cells by multiphoton intravital flow cytometry. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 11760–11765 (2007). A method using intravital flow cytometry for non-invasive detection of rare CTCs in vivo as they flow through the peripheral vasculature after intravenous injection of a tumour-specific fluorescent ligand in mice.

Hsieh, H. B. et al. High speed detection of circulating tumor cells. Biosens. Bioelectron. 21, 1893–1899 (2006).

Krivacic, R. T. et al. A rare-cell detector for cancer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 10501–10504 (2004).

Zheng, S. et al. Membrane microfilter device for selective capture, electrolysis and genomic analysis of human circulating tumor cells. J. Chromatogr. A 1162, 154–161 (2007).

Pinzani, P. et al. Isolation by size of epithelial tumor cells in peripheral blood of patients with breast cancer: correlation with real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction results and feasibility of molecular analysis by laser microdissection. Hum. Pathol. 37, 711–718 (2006).

Alix-Panabieres, C., Muller, V. & Pantel, K. Current status in human breast cancer micrometastasis. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 19, 558–563 (2007).

Alix-Panabieres, C. et al. Detection and characterization of putative metastatic precursor cells in cancer patients. Clin. Chem 53, 537–539 (2007). Using a novel technology called EPISPOT this paper describes that some CTCs in patients with localized prostate cancer secrete FGF2, a stem cell growth factor.

Smith, B. et al. Detection of melanoma cells in peripheral blood by means of reverse transcriptase and polymerase chain reaction. Lancet 338, 1227–1229 (1991).

Brakenhoff, R. H. et al. Sensitive detection of squamous cells in bone marrow and blood of head and neck cancer patients by E48 reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction. Clin. Cancer Res. 5, 725–732 (1999).

van Houten, V. M. et al. Molecular assays for the diagnosis of minimal residual head-and-neck cancer: methods, reliability, pitfalls, and solutions. Clin. Cancer Res. 6, 3803–3816 (2000).

Benoy, I. H. et al. Detection of circulating tumour cells in blood by quantitative real-time RT-PCR: effect of pre-analytical time. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 44, 1082–1087 (2006).

Nolan, T., Hands, R. E. & Bustin, S. A. Quantification of mRNA using real-time RT-PCR. Nature Protoc. 1, 1559–1582 (2006).

Quintela-Fandino, M. et al. Breast cancer-specific mRNA transcripts presence in peripheral blood after adjuvant chemotherapy predicts poor survival among high-risk breast cancer patients treated with high-dose chemotherapy with peripheral blood stem cell support. J. Clin. Oncol. 24, 3611–3618 (2006).

Xi, L. et al. Optimal markers for real-time quantitative reverse transcription PCR detection of circulating tumor cells from melanoma, breast, colon, esophageal, head and neck, and lung cancers. Clin. Chem 53, 1206–1215 (2007).

Wang, J. Y. et al. Molecular detection of circulating tumor cells in the peripheral blood of patients with colorectal cancer using RT-PCR: significance of the prediction of postoperative metastasis. World J. Surg. 30, 1007–1013 (2006).

Martin, K. J. et al. Linking gene expression patterns to therapeutic groups in breast cancer. Cancer Res. 60, 2232–2238 (2000).

Bai, V. U. et al. Identification of prostate cancer mRNA markers by averaged differential expression and their detection in biopsies, blood, and urine. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 104, 2343–2348 (2007).

de Cremoux, P. et al. Detection of MUC1-expressing mammary carcinoma cells in the peripheral blood of breast cancer patients by real-time polymerase chain reaction. Clin. Cancer Res. 6, 3117–3122 (2000).

Zieglschmid, V. et al. Combination of immunomagnetic enrichment with multiplex RT-PCR analysis for the detection of disseminated tumor cells. Anticancer Res. 25, 1803–1810 (2005).

Wu, C. H. et al. Development of a high-throughput membrane-array method for molecular diagnosis of circulating tumor cells in patients with gastric cancers. Int. J. Cancer 119, 373–379 (2006). A sensitive, high-throughput colorimetric membrane-array omitting cell enrichment and qPCR is reported using oligonucleotide probes and alkaline phosphatase detection for simultaneous detection of CTC target genes.

Chen, T. F. et al. CK19 mRNA expression measured by reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) in the peripheral blood of patients with non-small cell lung cancer treated by chemo-radiation: an independent prognostic factor. Lung Cancer 56, 105–114 (2007).

Xenidis, N. et al. Clinical relevance of circulating CK-19 mRNA-positive cells detected during the adjuvant tamoxifen treatment in patients with early breast cancer. Ann. Oncol. 18, 1623–1631 (2007).

Wang, J. Y. et al. Multiple molecular markers as predictors of colorectal cancer in patients with normal perioperative serum carcinoembryonic antigen levels. Clin. Cancer Res. 13, 2406–2413 (2007).

Liu, Z., Jiang, M., Zhao, J. & Ju, H. Circulating tumor cells in perioperative esophageal cancer patients: quantitative assay system and potential clinical utility. Clin. Cancer Res. 13, 2992–2997 (2007).

Hermanek, P., Sobin, L. H. & Wittekind, C. How to improve the present TNM staging system. Cancer 86, 2189–2191 (1999).

Singletary, S. E., Greene, F. L. & Sobin, L. H. Classification of isolated tumor cells: clarification of the 6th edition of the American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Manual. Cancer 98, 2740–2741 (2003).

Harris, L. et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology 2007 update of recommendations for the use of tumor markers in breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 25, 5287–5312 (2007).

Slade, M. J. & Coombes, R. C. The clinical significance of disseminated tumor cells in breast cancer. Nature Clin. Pract. Oncol. 4, 30–41 (2007).

Braun, S. et al. A pooled analysis of bone marrow micrometastasis in breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 353, 793–802 (2005). Pooled analysis of data from 12 European centres and one US centre, comprising 4,703 patients with primary breast cancer (that is, no signs of overt metastases), showing that the ∼30% of women with DTCs in their BM have an unfavourable clinical outcome.

Borgen, E. et al. Immunocytochemical detection of isolated epithelial cells in bone marrow: non-specific staining and contribution by plasma cells directly reactive to alkaline phosphatase. J. Pathol. 185, 427–434 (1998).

Braun, S. & Pantel, K. Biological characteristics of micrometastatic cancer cells in bone marrow. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 18, 75–90 (1999).

Borgen, E., Naume, B. & Nesland, J. M. Standardization of the immunocytochemical detection of cancer cells in BM and blood: I. Establishment of objective criteria of the evaluation of immunostained cells. Cytotherapy 1, 377–388 (1999).

Pierga, J. Y. et al. Clinical significance of immunocytochemical detection of tumor cells using digital microscopy in peripheral blood and bone marrow of breast cancer patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 10, 1392–1400 (2004).

Wiedswang, G. et al. Comparison of the clinical significance of occult tumor cells in blood and bone marrow in breast cancer. Int. J. Cancer 118, 2013–2019 (2006).

Benoy, I. H. et al. Real-time RT-PCR detection of disseminated tumour cells in bone marrow has superior prognostic significance in comparison with circulating tumour cells in patients with breast cancer. Br J. Cancer 94, 672–680 (2006).

Rack, B. K. et al. Circulating tumor cells (CTCs) in the peripheral blood of primary breast cancer patients. J. Clin. Oncol. 25, Abstract 10595 (2007).

Ntoulia, M. et al. Detection of Mammaglobin A-mRNA-positive circulating tumor cells in peripheral blood of patients with operable breast cancer with nested RT-PCR. Clin. Biochem 39, 879–887 (2006).

Xenidis, N. et al. Predictive and prognostic value of peripheral blood cytokeratin-19 mRNA-positive cells detected by real-time polymerase chain reaction in node-negative breast cancer patients. J. Clin. Oncol. 24, 3756–3762 (2006).

Ignatiadis, M. et al. Different prognostic value of cytokeratin-19 mRNA positive circulating tumor cells according to estrogen receptor and HER2 status in early-stage breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 25, 5194–5202 (2007). This clinical study shows for the first time that CTCs detected by a sensitive qPCR assay are of prognostic value in particular subgroups of early-stage breast cancer patients who carry tumours with a high-risk molecular profile.

Wolfrum, F., Vogel, I., Fandrich, F. & Kalthoff, H. Detection and clinical implications of minimal residual disease in gastro-intestinal cancer. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 390, 430–441 (2005).

Soeth, E. et al. Detection of tumor cell dissemination in pancreatic ductal carcinoma patients by CK 20 RT-PCR indicates poor survival. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 131, 669–676 (2005).

Hoffmann, A. C. et al. Survivin mRNA in peripheral blood is frequently detected and significantly decreased following resection of gastrointestinal cancers. J. Surg Oncol. 95, 51–54 (2007).

Demicheli, R., Retsky, M. W., Hrushesky, W. J. & Baum, M. Tumor dormancy and surgery-driven interruption of dormancy in breast cancer: learning from failures. Nature Clin. Pract. Oncol. 4, 699–710 (2007).

Wiedswang, G. et al. Isolated tumor cells in bone marrow three years after diagnosis in disease-free breast cancer patients predict unfavorable clinical outcome. Clin. Cancer Res. 10, 5342–5348 (2004). This clinical study demonstrates that DTCs in BM survive chemotherapy and persist for at least 3 years after surgical removal of the primary tumour. The presence of these dormant DTCs was associated with an increased risk of metastatic relapse.

Janni, W. et al. The persistence of isolated tumor cells in bone marrow from patients with breast carcinoma predicts an increased risk for recurrence. Cancer 103, 884–891 (2005).

Braun, S. et al. Lack of effect of adjuvant chemotherapy on the elimination of single dormant tumor cells in bone marrow of high-risk breast cancer patients. J. Clin. Oncol. 18, 80–86 (2000).

Slade, M. J. et al. Persistence of bone marrow micrometastases in patients receiving adjuvant therapy for breast cancer: results at 4 years. Int. J. Cancer 114, 94–100 (2005).

Janni, W. J. et al. Persistence of disseminated tumor cells in bone marrow of breast cancer patients predicts increased risk for relapse- results of pooled European data. J. Clin. Oncol. 24, Abstract 10083 (2006).

Budd, G. T. et al. Circulating tumor cells versus imaging--predicting overall survival in metastatic breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 12, 6403–6409 (2006).

Mueller, V. et al. Prospective monitoring of circulating tumor cells in breast cancer patients treated with primary systemic therapy—A translational project of the German Breast Group study GeparQuattro. J. Clin. Oncol. 25, Abstact 21085 (2007).

Braun, S. et al. Cytokeratin-positive cells in the bone marrow and survival of patients with stage, I., II, or III breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 342, 525–533 (2000).

Klein, C. A. et al. Comparative genomic hybridization, loss of heterozygosity, and DNA sequence analysis of single cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 96, 4494–4499 (1999).

Schmidt-Kittler, O. et al. From latent disseminated cells to overt metastasis: genetic analysis of systemic breast cancer progression. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 7737–7742 (2003).

Schardt, J. A. et al. Genomic analysis of single cytokeratin-positive cells from bone marrow reveals early mutational events in breast cancer. Cancer Cell 8, 227–239 (2005).

Gangnus, R., Langer, S., Breit, E., Pantel, K. & Speicher, M. R. Genomic profiling of viable and proliferative micrometastatic cells from early-stage breast cancer patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 10, 3457–3464 (2004).

Klein, C. A. et al. Genetic heterogeneity of single disseminated tumour cells in minimal residual cancer. Lancet 360, 683–689 (2002).

Gray, J. W. Evidence emerges for early metastasis and parallel evolution of primary and metastatic tumors. Cancer Cell 4, 4–6 (2003).

Schmidt, H. et al. Asynchronous growth of prostate cancer is reflected by circulating tumor cells delivered from distinct, even small foci, harboring loss of heterozygosity of the PTEN gene. Cancer Res. 66, 8959–8965 (2006).

Fidler, I. J. The pathogenesis of cancer metastasis: the 'seed and soil' hypothesis revisited. Nature Rev. Cancer 3, 453–458 (2003).

Fizazi, K. et al. High detection rate of circulating tumor cells in blood of patients with prostate cancer using telomerase activity. Ann. Oncol. 18, 518–521 (2007).

Yie, S. M., Luo, B., Ye, N. Y., Xie, K. & Ye, S. R. Detection of Survivin-expressing circulating cancer cells in the peripheral blood of breast cancer patients by a RT-PCR ELISA. Clin. Exp Metastasis 23, 279–289 (2006).

Solakoglu, O. et al. Heterogeneous proliferative potential of occult metastatic cells in bone marrow of patients with solid epithelial tumors. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 99, 2246–2251 (2002).

Pierga, J. Y. et al. Clinical significance of proliferative potential of occult metastatic cells in bone marrow of patients with breast cancer. Br. J. Cancer 89, 539–545 (2003).

Mehes, G., Witt, A., Kubista, E. & Ambros, P. F. Circulating breast cancer cells are frequently apoptotic. Am. J. Pathol. 159, 17–20 (2001).

Fehm, T. et al. Determination of HER2 status using both serum HER2 levels and circulating tumor cells in patients with recurrent breast cancer whose primary tumor was HER2 negative or of unknown HER2 status. Breast Cancer Res. 9, R74 (2007).

Schmidt, H. et al. Frequent detection and immunophenotyping of prostate-derived cell clusters in the peripheral blood of prostate cancer patients. Int. J. Biol. Markers 19, 93–99 (2004).

Braun, S. et al. ErbB2 overexpression on occult metastatic cells in bone marrow predicts poor clinical outcome of stage I–III breast cancer patients. Cancer Res. 61, 1890–1895 (2001).

Wulfing, P. et al. HER2-positive circulating tumor cells indicate poor clinical outcome in stage I to III breast cancer patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 12, 1715–1720 (2006). The first description of the prognostic value of ERBB2-positive CTCs in non-metastatic breast cancer. Furthermore, a discrepancy of the ERBB2-status between the primary tumour and the CTCs was reported.

Meng, S. et al. HER-2 gene amplification can be acquired as breast cancer progresses. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 9393–9398 (2004). The acquisition of ERBB2 gene amplification in CTCs was reported for breast cancer patients whose primary tumor was ERBB2-negative. Herceptin-containing therapy achieved complete response and partial response in a few patients.

Heiss, M. M. et al. Minimal residual disease in gastric cancer: evidence of an independent prognostic relevance of urokinase receptor expression by disseminated tumor cells in the bone marrow. J. Clin. Oncol. 20, 2005–2016 (2002).

Meng, S. et al. uPAR and HER-2 gene status in individual breast cancer cells from blood and tissues. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 17361–17365 (2006).

Aguirre-Ghiso, J. A. Models, mechanisms and clinical evidence for cancer dormancy. Nature Rev. Cancer 7, 834–846 (2007).

Koebel, C. M. et al. Adaptive immunity maintains occult cancer in an equilibrium state. Nature 450, 903–907 (2007). This experimental study provides evidence for an active role of the immune system in maintaining dormancy of tumour cells. In a carcinogen-induced tumour model, the immune system of naive mice restrained cancer growth for extended time periods.

Wicha, M. S. Cancer stem cells and metastasis: lethal seeds. Clin. Cancer Res. 12, 5606–5607 (2006).

Bao, S. et al. Glioma stem cells promote radioresistance by preferential activation of the DNA damage response. Nature 444, 756–760 (2006).

Balic, M. et al. Most early disseminated cancer cells detected in bone marrow of breast cancer patients have a putative breast cancer stem cell phenotype. Clin. Cancer Res. 12, 5615–5621 (2006). Using multiple immunostaining of DTCs that are present in the BM of breast cancer patients, this is the first report indicating that many DTCs have a putative cancer stem cell phenotype (that is, CD44+/CD24−).

Liu, R. et al. The prognostic role of a gene signature from tumorigenic breast-cancer cells. N. Engl. J. Med. 356, 217–226 (2007).

Al-Hajj, M., Wicha, M. S., Benito-Hernandez, A., Morrison, S. J. & Clarke, M. F. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 3983–3988 (2003).

Ginestier, C., Hur, M. & Charafe-Jauffret, E. ALDH1 is a marker of normal and malignant human mammary stem cells and a predictor of poor clinical outcome. Cell Stem Cell 1, 555–567 (2007).

Silva, J. et al. Circulating Bmi-1 mRNA as a possible prognostic factor for advanced breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res. 9, R55 (2007).

Kaplan, R. N. et al. VEGFR1-positive haematopoietic bone marrow progenitors initiate the pre-metastatic niche. Nature 438, 820–827 (2005).

Patocs, A. et al. Breast-cancer stromal cells with TP53 mutations and nodal metastases. N. Engl. J. Med. 357, 2543–2551 (2007).

Weber, F. et al. Microenvironmental genomic alterations and clinicopathological behavior in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. JAMA 297, 187–195 (2007).

Piccart-Gebhart, M. J. et al. Trastuzumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-positive breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 353, 1659–1672 (2005).

Romond, E. H. et al. Trastuzumab plus adjuvant chemotherapy for operable HER2-positive breast cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 353, 1673–1684 (2005).

Wolff, A. C. et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology/College of American Pathologists guideline recommendations for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 testing in breast cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 25, 118–145 (2007).

Fehm, T. et al. Presence of apoptotic and nonapoptotic disseminated tumor cells reflects the response to neoadjuvant systemic therapy in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 8, R60 (2006).

Roetger, A. et al. Selection of potentially metastatic subpopulations expressing c-erbB-2 from breast cancer tissue by use of an extravasation model. Am. J. Pathol. 153, 1797–1806 (1998).

Brandt, B. H. et al. c-erbB-2/EGFR as dominant heterodimerization partners determine a motogenic phenotype in human breast cancer cells. FASEB J. 13, 1939–1949 (1999).

Thor, A. D., Edgerton, S. M., Liu, S., Moore, D. H. 2nd & Kwiatkowski, D. J. Gelsolin as a negative prognostic factor and effector of motility in erbB-2-positive epidermal growth factor receptor-positive breast cancers. Clin. Cancer Res. 7, 2415–2424 (2001).

Li, Y. M. et al. Upregulation of CXCR4 is essential for HER2-mediated tumor metastasis. Cancer Cell 6, 459–469 (2004).

Brandt, B. et al. Isolation of blood-borne epithelium-derived c-erbB-2 oncoprotein-positive clustered cells from the peripheral blood of breast cancer patients. Int. J. Cancer 76, 824–828 (1998).

Becker, S., Becker-Pergola, G., Wallwiener, D., Solomayer, E. F. & Fehm, T. Detection of cytokeratin-positive cells in the bone marrow of breast cancer patients undergoing adjuvant therapy. Breast Cancer Res. Treat 97, 91–96 (2006).

Becker, S., Solomayer, E., Becker-Pergola, G., Wallwiener, D. & Fehm, T. Primary systemic therapy does not eradicate disseminated tumor cells in breast cancer patients. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 106, 239–243 (2007).

Steeg, P. S. Tumor metastasis: mechanistic insights and clinical challenges. Nature Med. 12, 895–904 (2006).

Ma, L., Teruya-Feldstein, J. & Weinberg, R. A. Tumour invasion and metastasis initiated by microRNA-10b in breast cancer. Nature 449, 682–688 (2007).

Tavazoie, S. F. et al. Endogenous human microRNAs that suppress breast cancer metastasis. Nature 451, 147–152 (2008).

Hunter, K. Host genetics influence tumour metastasis. Nature Rev. Cancer 6, 141–146 (2006).

Godfrey, T. E. & Kelly, L. A. Development of quantitative reverse transcriptase PCR assays for measuring gene expression. Methods Mol. Biol. 291, 423–445 (2005).

de Kok, J. et al. Normalization of gene expression measurements in tumor tissues: comparison of 13 endogenous control genes. Lab. Invest. 85, 154–159 (2005).

Kowalewska, M., Chechlinska, M., Markowicz, S., Kober, P. & Nowak, R. The relevance of RT-PCR detection of disseminated tumour cells is hampered by the expression of markers regarded as tumour-specific in activated lymphocytes. Eur J. Cancer 42, 2671–2674 (2006).

Dandachi, N. et al. Critical evaluation of real-time reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction for the quantitative detection of cytokeratin 20 mRNA in colorectal cancer patients. J. Mol. Diagn. 7, 631–637 (2005).

Braakhuis, B. J., Tabor, M. P., Kummer, J. A., Leemans, C. R. & Brakenhoff, R. H. A genetic explanation of Slaughter's concept of field cancerization: evidence and clinical implications. Cancer Res. 63, 1727–1730 (2003). Using genetic analyses of tumour and surrounding mucosa, a model for squamous cancers was established, strongly focused on the role of the epithelial stem cell.

Watson, M. A. et al. Isolation and molecular profiling of bone marrow micrometastases identifies TWIST1 as a marker of early tumor relapse in breast cancer patients. Clin. Cancer Res. 13, 5001–5009 (2007).

Apostolaki, S. et al. Circulating HER2 mRNA-positive cells in the peripheral blood of patients with stage I and II breast cancer after the administration of adjuvant chemotherapy: evaluation of their clinical relevance. Ann. Oncol. 18, 851–858 (2007).

Acknowledgements

We thank I. Alpers for support in the manuscript preparation and D. Kemming for the technical assistance in art work. This work was supported by the European Commission (DISMAL project, contract no. LSHC-CT-2005-018911 and OVCAD project, contract no. LSHC-CT-2005-018698), Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, Bonn, Germany and the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Related links

Related links

DATABASES

National Cancer Institute

National Cancer Institute Drug Dictionary

FURTHER INFORMATION

Glossary

- Ferrofluid

-

A suspension of 10 nm colloidal iron particles stabilized by polymers.

- Pharmacodynamics

-

The effects on the biochemistry of the body resulting from treatment with a drug or combination of drugs.

- ELISPOT

-

An antibody-capture-based method for enumerating specific T cells (CD4+ and CD8+) that secrete a particular cytokine (often interferon-γ).

- Iliac crest

-

The outer rim of the pelvic bone, accessed for needle aspiration of bone marrow.

- Anoikis

-

Apoptosis induced in isolated cells leaving an epithelial tissue.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pantel, K., Brakenhoff, R. & Brandt, B. Detection, clinical relevance and specific biological properties of disseminating tumour cells. Nat Rev Cancer 8, 329–340 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc2375

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/nrc2375

This article is cited by

-

Age-Related Features of the Response of Cancer Stem Cells and T Cells in Experimental Lung Cancer

Bulletin of Experimental Biology and Medicine (2024)

-

Label-free cancer cell separation from whole blood on centrifugal microfluidic platform using hydrodynamic technique

Microfluidics and Nanofluidics (2024)

-

Highly stable integration of graphene Hall sensors on a microfluidic platform for magnetic sensing in whole blood

Microsystems & Nanoengineering (2023)

-

Metastasis suppressor genes and their role in the tumor microenvironment

Cancer and Metastasis Reviews (2023)

-

Comparative application of microfluidic systems in circulating tumor cells and extracellular vesicles isolation; a review

Biomedical Microdevices (2023)