Abstract

High sensitivity and specificity are two desirable features in biomedical imaging. Raman imaging has surfaced as a promising optical modality that offers both. Here we report the design and synthesis of a group of near-infrared absorbing 2-thienyl-substituted chalcogenopyrylium dyes tailored to have high affinity for gold. When adsorbed onto gold nanoparticles, these dyes produce biocompatible SERRS nanoprobes with attomolar limits of detection amenable to ultrasensitive in vivo multiplexed tumour and disease marker detection.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) is rapidly gaining interest in the field of biomedical imaging1,2,3. By adsorbing a molecule on a noble metal surface, the weak Raman scattering of a molecule (only 1 in ~107 photons induces Raman scattering) is massively amplified (enhancement factor 107−1010)4,5,6. This phenomenon creates a spectroscopic technique that not only has high sensitivity (10−9–10−12 M limits of detectability), but also the potential for multiplexing capabilities due to the unique vibrational structure of adsorbed molecules7,8,9. These characteristics have prompted the use of SERS in a wide array of biomedical imaging applications2,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17.

Orders-of-magnitude higher sensitivities (10−12–10−14 M) can be achieved utilizing Raman reporters that are in resonance with the incident laser, thereby producing surface-enhanced resonance Raman scattering (SERRS) nanoprobes18,19,20. Absorption of light by biological tissue is minimal in the near-infrared (NIR) window and, as a consequence, most optical biomedical applications use NIR detection lasers. While a great deal of attention has been given to dye molecules that absorb light in the visible region, less work has been devoted to developing Raman reporters with absorption maxima that are resonant with NIR detection lasers. The most common Raman reporters are members of the cyanine class of dyes21.

Herein we report thiophene-substituted chalcogenopyrylium (CP) dyes as a new class of ultra bright, NIR-absorbing Raman reporters. One notable feature of the pyrylium dyes is the ease in which a broad range of absorptivities can be accessed, and consequently be matched with the NIR light source by careful tuning of the dye’s optical properties. Specifically, the large differences in absorption maxima introduced by switching the chalcogen atom is a useful property of this dye class22. Another important consideration is the affinity of the reporter for the surface of gold. Since the SERS effect decreases exponentially as a function of distance from the nanoparticle23, it is important that the Raman reporter is near the gold surface. The 2-thienyl substituent provides a novel attachment point to gold for Raman reporters. The 2-thienyl group is not only part of the dye chromophore, but also can be rigorously coplanar with the rest of the chromophore24. This allows the dye molecules to be in close proximity to the nanoparticle surface, creating a brighter SERRS signal.

Results

Chalcogenopyrylium dye synthesis and characterization

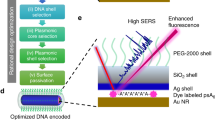

Cationic CP dyes 1–3, with absorption maxima near the 785-nm emission of the detection laser were synthesized as outlined in Fig. 1a. The addition of MeMgBr to the known chalcogenopyranones25 (4, 6), followed by dehydration with the appropriate acid (HZ), yields 4-methyl pyrylium compounds (5, 7) with the desired counterion (PF6− or ClO4−)22,26,27. The condensation of 7 with N,N-dimethylthioformamide in Ac2O, and subsequent hydrolysis of the intermediate iminium salt yields the (chalcogenopyranylidene)acetaldehyde 8, the penultimate compound leading to trimethine CP dyes22. Condensation of 4-methylpyrylium salt 5 and the (chalcogenopyranylidene)acetaldehyde 8 bearing the desired R groups and chalcogen atom in hot Ac2O (ref. 26) forms the final dye compounds 1−3 that are substituted with 2-phenyl or 2-thienyl groups, and different combinations of chalcogen atoms (S or Se) (Table 1). The Cl− and Br− counterions of dye 1a were accessed by treating the PF6− salts with an Amberlite ion exchange resin.

(a) Reaction scheme for the synthesis of pyrylium-based SERRS reporters (1−3). (b) A 60-nm gold core (yellow) encapsulated in a 15-nm thick chalcogenopyrylium dye (red; Ph, phenyl)-containing silica shell (blue). The structure, yields and optical properties of the different chalcogenopyrylium-based Raman reporters are shown in the table.

SERRS nanoprobe synthesis and characterization

CP dyes 1−3 were dissolved in dry N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF), at a concentration between 1.0 and 10 mM, and were subsequently used to generate the SERRS nanoprobes. The SERRS nanoprobes consist of a gold core onto which the SERRS reporter is adsorbed, which is then protected by an encapsulating silica layer (Fig. 1b, Table 1). The pyrylium-based SERRS nanoprobes were synthesized by encapsulating 60-nm spherical citrate-capped gold nanoparticles via a modified Stöber procedure28,29,30 in the presence of the reporter. After 25 min, the reaction was quenched by the addition of ethanol and the SERRS nanoprobes were collected through centrifugation. Typically, the as-synthesized SERRS nanoprobes had a mean diameter of ~100 nm (non-aggregated; Supplementary Figs 1 and 2).

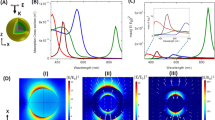

Effect of counterion on colloidal stability and SERRS signal

In previous reports, the dye counterion was shown to affect the structural and electronic properties of polymethine dyes31 and the solubility of CP dyes32. Since SERRS is highly dependent on these factors, we evaluated the effect of the counterion (Z−) on the SERRS spectrum, intensity and colloidal stability of the pyrylium-based SERRS nanoprobes. We compared chloride (Cl−), bromide (Br−), perchlorate (ClO4−) and hexafluorophosphate (PF6−) as counterions for CP dye 1a. The SERRS nanoprobes were synthesized in the presence of equimolar amounts (10 μM) of CP dye 1a·Z− (where Z−=Cl−, Br−, ClO4− or PF6−). The counterion introduces almost no difference in optical properties such as absorption maxima and extinction coefficient. Furthermore, with the exception of the chloride counterion, the Raman shifts and intensity of 1a were minimally affected by the different counterions (Fig. 2a). The colloidal stability, however, was shown to be highly counterion dependent (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1). The least chaotropic counterion, Cl−, strongly destabilized the gold colloids and caused aggregation of SERRS nanoprobes utilizing 1a as a reporter as evidenced by the strong absorption between 700 and 900 nm. The strongest chaotropic anion, PF6−, did not affect colloidal stability during the synthesis of SERRS nanoprobes as evidenced by the strong absorption at 540 nm and low absorbance between 700 and 900 nm (monomeric 60-nm spherical gold nanoparticles have an absorption maximum around 540 nm). Since the PF6− anion induced the least nanoparticle aggregation, it was used for further SERRS experiments.

(a) The effect of the counterion (Z−) on SERRS intensity (785 nm, 50 μW, 1.0 s acquisition time, 5 × objective). Inset: Structure of CP dye 1a (Ph, phenyl). (b) Effect of counterion on the colloidal stability of CP-dye 1a-based SERRS nanoprobes (n=3, error bars represent s.d.; See also Supplementary Fig. 1; Supplementary Table 1).

Effect of increased affinity on colloidal stability and SERRS signal

We also examined the SERRS signal intensity as a function of the number of sulphur atoms in the dye. Sulphur-containing functionality has been used frequently to adhere molecules to gold33, with several reports using thiol or lipoic acid functional groups to add sulphur-containing functionality21,34. In our structures, 2-thienyl groups attached to the 2- and 6- positions of the dye were used to bind the dyes to the gold surface. We also explored the impact of the chalcogen atoms in the CP core, switching a Se (1a and 2a) to S (1b and 2b). The chalcogen switch was used to increase semicovalent interactions with the gold surface, and also to create a chromophore that had a more resonant absorption with the 785-nm detection laser (Table 1). CP dyes 1−3 were used at a final concentration of 1.0 μM, which prevented nanoparticle aggregation for dye 3. Fig. 3a shows the molecular structures of the CP dyes. The SERRS intensity of the different as-synthesized pyrylium-based SERRS nanoprobes, which were synthesized at equimolar reporter concentrations, were measured at equimolar SERRS nanoprobe concentrations at low laser power to prevent CCD-saturation (50 μW, 1.0 s acquisition time, 5 × objective). We specifically focused on the 1,600 cm−1 peak, which corresponds to aromatic ring stretching modes; and is a mode shared by CP dyes 1–3. The SERRS signal intensity of the 1,600 cm−1 peak increased significantly as the number of 2-thienyl substituents increased (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Table 1) without causing significant aggregation (Fig. 3c, Supplementary Fig. 2 and Supplementary Table 1). Thus, 3 produced the highest SERRS signal, which was significantly more intense than 2a/2b or 1a/1b (P<0.05) and 2a/2b were significantly more intense than 1a/1b (P<0.05). There was a less noticeable, but significant, increase from the chalcogen switch in the core (1a/1b and 2a/2b being significantly different (P<0.05)). This strongly supports the hypothesis that 2-thienyl groups are an effective means of adhering dyes to gold, resulting in brighter SERRS nanoprobes.

(a) Molecular structures of the adsorbed CP dyes (1–3) arranged by increased number of 2-thienyl substituents (Ph, phenyl). (b) SERRS spectra of the CP-based SERRS nanoprobes. The SERRS spectra were baseline corrected to allow proper comparison. (For the non-baseline corrected spectra see Supplementary Fig. 3). Inset: intensity of the 1,600 cm−1 peak (n=3; error bars represent s.d., *P<0.05; an unpaired Student’s t-test was performed). (c) Colloidal stability of the CP-based SERRS nanoprobes as determined by LSPR measurements (n=3; error bars represent s.d.; See also Supplementary Fig. 2; Supplementary Table 1).

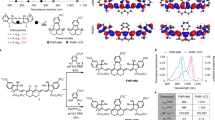

Comparison of CP-dye 3 with a cyanine-based SERRS reporter

To assess the quality of our optimized nanoprobe, thiopyrylium dye 3 and commercially available IR792 (Fig. 4a), which has been previously used to generate surface-enhanced resonance Raman scattering nanoprobes35, were studied. A direct comparison of the nanoprobes synthesized in the presence of equimolar (1.0 μM) amounts of 3 and IR792 shows a five- to sixfold higher signal for nanoprobes generated with dye 3 (Fig. 4b). It is interesting to note that a fluorescence background is minimal in the SERRS spectra of the CP- and cyanine-based SERRS nanoprobes (Supplementary Fig. 3). Whereas fluorescence interference would not be expected from CP dyes containing heavy chalcogens that enhance intersystem crossing36, fluorescence interference could be expected for the cyanine dye IR792. In fact, when equimolar amounts of the CP dyes 1−3 and IR792 were incorporated in silica (without gold nanoparticle), IR792 demonstrated strong fluorescence when excited at 785 nm (50 μW, 1.0 s acquisition time), while minimal fluorescence was observed for CP 1–3. As shown in Fig. 4b and Supplementary Fig. 3, the fluorescence interference of the cyanine dye IR792 is minimal in its SERRS spectrum. This is due to quenching effects near the surface of the nanoparticle37.

(a) Structure of the resonant dye IR792 and chalcogenopyrylium dye 3. (b) SERRS intensity of an equimolar amount of an IR792-based SERRS nanoprobe and a 3-based SERRS nanoprobe that were synthesized with an equimolar amount of the dyes. (c) Limits of detection of the IR792- (cyan) and 3- (red) based SERRS nanoprobes were performed in triplicate and determined to be 1.0 fM and 100 aM, respectively (error bars represent s.d.; see also Supplementary Fig. 4).

A concentration series of the as-synthesized SERRS nanoprobes was generated in triplicate manner (Supplementary Fig. 4) to determine the limit of detection (LOD) of both nanoprobes. Fig. 4c shows the LOD for IR792-based nanoprobes to be 1.0 fM, while 3-based nanoprobes had a 10-fold lower LOD, 100 aM. To our knowledge this is the lowest reported LOD utilizing a biologically relevant NIR excitation source. We also evaluated the serum stability of the 3-based SERRS nanoprobe. The SERRS nanoprobe was shown to be serum stable (no significant difference between t=1 h and t=48 h) for at least 48 h (Supplementary Fig. 5; Supplementary Methods). This is supported by a study by Thakor et al.38 who have shown that SERS nanoparticles of similar size and composition remain stable in vivo for >2 weeks.

In vivo comparison of EGFR-targeted 3- or IR792-SERRS nanoprobes

The ability of our SERRS nanoprobe to delineate tumour tissue in vivo was assessed by utilizing CP dye 3 and IR792-based SERRS nanoprobes functionalized with an epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)-targeting antibody. Equimolar amounts (15 fmol g−1) of these two EGFR-targeted nanoprobes were injected intravenously into athymic nude mice that had been inoculated 2 weeks prior with the EGFR-overexpressing cell line A431 (1 × 106 cells). After 18 h, the skin around the tumour was carefully peeled back and multiplexed Raman imaging of the tumour site and surrounding tissue was performed (Figs 5 and 6). A Raman map was generated and the signals from the multiplexed SERRS nanoprobes were deconvoluted by applying a direct classical least square algorithm (DCLS)7. The SERRS signal from both nanoprobes was more intense for the tumour site than for the surrounding tissue, showing that the EGFR-targeted SERRS nanoprobes had selectively localized at the tumour site. The SERRS signal intensity in the tumour was approximately 3 × higher for the 3-based SERRS nanoprobe than for the otherwise identical IR792-based SERRS nanoprobe. Ex vivo multiplexed Raman imaging of the tumour showed Raman signal of the EGFR-targeted SERRS nanoprobes throughout the tumour with the exception of a hypointense Raman region in the centre of the tumour. Hematoxyolin and eosin and immunohistochemical staining for EGFR was performed (Supplementary Methods) and revealed that the hypointense Raman region corresponded with an area of necrosis, which explains the lack of SERRS nanoprobe accumulation and decreased Raman signal. In addition, to validate EGFR targeting, we injected A431-tumour-bearing mice with cetuximab (50 pmol g−1) 3 h before injection with the EGFR-targeted SERRS nanoprobes. Preblocking of EGFR by cetuximab resulted in decreased accumulation of the EGFR-targeted SERRS nanoprobes within the tumours of animals that were injected with cetuximab before EGFR-targeted SERRS nanoprobe injection as compared with animals that were injected with EGFR-targeted SERRS nanoprobes and were not preinjected with cetuximab (Supplementary Fig. 6).

Female nude mice (n=5) bearing A431 xenograft tumours were injected intravenously via tail vein with an equimolar amount of EGFR-antibody (cetuximab)-conjugated IR792- and CP 3-based SERRS nanoprobes (15 fmol g−1 per probe; total injected dose: 30 fmol g−1). After 18 h, the tumours were imaged in situ by Raman (10 mW, 1.5 s acquisition time, 5 × objective). The chalcogenopyrylium dye 3-based SERRS nanoprobe (red) provided ~3 × higher signal than the IR792-based SERRS nanoprobe (cyan; 22.442 versus 7.313 cps cm−2, respectively). All scale bars represent 2.0 mm.

The excised tumour was scanned by Raman imaging (10 mW, 1.5 s acquisition time, 5 × objective), fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, and processed for hematoxyolin and eosin staining and anti-EGFR immunohistochemistry. With the exception of a hypointense Raman region in the centre of the tumour, the tumour homogenously expressed EGFR and the EGFR-targeted SERRS nanoprobes had accumulated throughout the tumour. The hypointense Raman area corresponds to a highly necrotic region within the tumour, which explains the lack of SERRS nanoprobe accumulation and decreased Raman signal. All scale bars represent 1.0 mm.

Discussion

Effective biomedical imaging requires low limits of detection and high specificity for biological targets. Raman imaging has surfaced as an optical imaging modality that has the promise to enable both. While the Raman effect is relatively weak (1 in 107 photons), the Raman scattering cross-section of a molecule can be massively amplified by noble metal surfaces4,5,6. Here we demonstrated that rational SERRS reporter design afforded SERRS nanoprobes with unprecedented limits of detection: 100 aM. This is, to the best of our knowledge, the lowest reported limit of detection at near-real-time detection (≤2.0 s acquisition times) for SERRS nanoprobes that are compatible with a NIR light source. As a comparison, non-resonant SERS nanoprobes are in the 0.1−1.0 pM range (1,000−10,000-fold less sensitive)2, while reported detection limits of SERRS nanoprobes are >17 fM at near-real-time detection39. Others have reported a 0.4 fM detection limit; however, this was acquired through cumulative data acquisition with an acquisition time ≥60 s, which is not practical for biomedical imaging applications35.

We believe the unprecedented limit of detection of our novel SERRS nanoprobe is due to several factors. First, we demonstrate that rational design and optimization of the SERRS reporter is important to achieve efficient ‘loading’ on the nanoparticle. Our results demonstrate that the counterion and gold surface affinity are important considerations. For instance, while the chaotropic PF6− anions stabilized the dye–nanoparticle system during silica shell formation in ethanol, the system becomes more destabilized with Cl− (more kosmotropic) ions present. Chloride-induced aggregation of colloidal dispersions in relation to SERS has been studied. Natan and colleagues40 demonstrated that the strongest enhancements were obtained from aggregates with effective diameters of <200 nm and aggregates with sizes >200 nm did not generate appreciable SERS intensities. The aggregates that were induced by the chloride counterion in our system were >200 nm (Supplementary Fig. 1), which might explain the reduced SERRS signal when chloride is used as a counterion. Others have shown that the kosmotropic chloride ion could induce reorientation of the dye on the surface, which could also contribute to the reduced SERRS intensities41. However, while we did observe a decrease in the SERRS signal intensity when chloride is present, we did not find any appreciable differences between the Raman spectra of the dyes when different counterions were used, which would have been expected if the molecule had reoriented on the surface. Since the most chaotropic counterion, PF6−, induced the least aggregation and generated robust SERRS signal intensities, we used PF6− as a counterion.

Next, we showed that an increase in affinity of the SERRS reporter for the gold nanoparticle surface via incorporation of 2-thienyl functional groups considerably increased the SERRS signal without inducing aggregation. Others have reported the functionalization of NIR dyes with thiol or lipoic acid functional groups. In contrast to a 2-thienyl substituent, thiol and lipoic acid functional groups offer no benefit to the optical properties of the dye, and as a tether, do not allow the dye to be as close to the gold surface34. Moreover, based on the absorption spectra of reported lipoic acid-modified cyanine dye–gold nanoparticle conjugates, it is clear that lipoic acid-modified dyes promote aggregation21.

Finally, the strategy chosen to stabilize the SERRS nanoprobe is a key factor. Others have reported using either surfactants or thiolated polymers to stabilize their SERRS nanoparticles35,39,42. However, such stabilizing agents compete with the SERRS reporter for the surface of the nanoparticle, which leads to lower SE(R)RS-signal. We achieved very low limits of detection by using a primerless silication procedure in which the silica not only served as a stabilizing agent, but also as a matrix to contain our optimized CP-based SERRS reporter. Since silica has much lower affinity for the gold than the applied SERRS reporters, attomolar limits of detection were achieved.

The CP dyes represent a new class of SERRS reporters. Selection of the right combination of chaotropic counterions and increased affinity of the SERRS reporter for the gold nanoparticle’s surface produces stable SERRS nanoprobes with exceptionally low limits of detection (attomolar range). The low limit of detection (that is, close to single nanoparticle detection) in combination with the high resolution of Raman imaging enables highly sensitive and specific near real-time tumour delineation and, as a result of the fingerprint-like spectra of the different SERRS nanoprobes, can offer multiplexed disease marker detection in vivo.

Methods

Materials

Chalcogenopyrylium dye synthesis and characterization. All reactions were performed open to air. Concentration in vacuo was performed on a rotary evaporator. NMR spectra were recorded at 300 or 500 MHz for 1H and at 75.5 MHz for 13C with residual solvent signal as internal standard. If a mixture of CD2Cl2 and CD3OD was used to acquire 1H NMR, the peak for CH2Cl2 was used as the internal standard. UV/VIS-near-IR spectra were recorded in quartz cuvettes with a 1-cm path length. Melting points were determined with a capillary melting point apparatus and are uncorrected. Non-hygroscopic compounds have a purity of ≥95% as determined by elemental analyses for C, H and N. Experimental values of C, H and N are within 0.3% of theoretical values. 13C NMR was not recorded for pyrylium dyes due to limited solubility in common NMR solvents. Chalcogenopyranones25 4 and 6 were made according to literature procedures as were 4-methylchalcogenopyrylium compounds 5 and 7 (refs 22, 25, 26, 27).

Preparation of 4-(2,6-di(thiophen-2-yl)-4H-thiopyran-4ylidene)acetaldehyde ( 8 , Y=S, R2=2-thienyl). 4-Methyl-2,6-di(thiophen-2-yl)thiopyrylium hexafluorophosphate (0.350 g, 0.833 mmol), N,N-dimethylthioformamide (0.213 ml, 2.50 mmol) and Ac2O (3.0 ml) were combined in a small round-bottom flask and heated at 95 °C for 1 h. After cooling to ambient temperature an additional portion of Ac2O (2.0 ml) was added and the solution diluted with ether. The formed iminium salt was allowed to precipitate in the freezer overnight, and then isolated by filtration to yield a bright orange solid. This solid was dissolved in CH3CN (3.0 ml) and saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (3.0 ml) was added. This mixture was heated to 80 °C over 15 min, and kept at that temperature for 30 min. After diluting with H2O (30 ml) the product was extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 50 ml), dried with Na2SO4 and purified on SiO2 with a 10% EtOAc/CH2Cl2 eluent (Rf=0.71) to yield a yellow oil that was recrystallized in CH2Cl2/hexanes to yield 0.219 g (87%) of a yellow crystalline solid, mp 143–144 °C: 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.84 (d, 1 H, J=6.0 Hz), 8.26 (s, 1 H), 7.45-7.39 (m, 4 H), 7.13-7.11 (m, 2 H), 6.88 (s, 1 H), 5.72 (d, 1 H, J=6.5 Hz); 13C NMR (75.5 MHz, CDCl3) δ 188.05, 146.43, 139.36, 139.07, 137.33, 136.65, 128.16, 127.78, 127.58, 126.30, 126.01, 122.48, 117.63, 117.48; HRMS (ESI) m/z 302.9971 (calculated for C15H10OS3+H+: 302.9967).

Preparation of 4-(2,6-diphenyl-4H-selenopyran-4ylidene)acetaldehyde ( 8 , Y=Se, R2=Ph). 4-Methyl-2,6-di(phenyl)selenopyrylium hexafluorophosphate (0.200 g, 0.439 mmol), N,N-dimethylthioformamide (0.112 ml, 1.32 mmol) and Ac2O (4.0 ml) were added to a round-bottom flask and heated at 95 °C for 90 min. After cooling to room temperature CH3CN (4.0 ml) was added and the product precipitated by addition of ether and chilling overnight in the freezer. The iminium salt was isolated by filtration, and hydrolysed by dissolving in CH3CN (4.0 ml), adding saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (4.0 ml) and heating the mixture to 80 °C over a 15 min period. The reaction was maintained at this temperature for 30 min, after which the reaction was diluted with H2O (50 ml), the product extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 30 ml), dried with MgSO4 and after concentration purified on SiO2 with first a CH2Cl2 and then a 10% EtOAc/CH2Cl2 (Rf=0.70) eluent to yield 0.122 g (82%) of an orange oil: 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ 10.11 (d, 1 H, J=10.5 Hz), 8.32 (s, 1 H), 7.62-7.46 (m, 9 H), 7.00 (s, 1 H), 5.88 (d, 1 H, J=11.0 Hz); 13C NMR (75.5 MHz, CDCl3) δ 188.69, 148.44, 147.01, 146.03, 138.65, 138.40, 129.96, 129.90, 129.14, 126.62, 126.44, 126.37, 126.31, 125.67, 120.57, 120.48; HRMS (ESI) m/z 339.0292 (calculated for C19H14O80Se+H+: 339.0283).

Preparation of 4-(3-(2,6-diphenyl-4H-selenopyran-4-ylidene)prop-1-enyl)-2,6-diphenylselenopyrylium ( 1a ) (CAS Registry Number: 51848-65-8). PF6− 4-Methyl-2,6-di(phenyl)selenopyrylium hexafluorophosphate (0.190 g, 0.417 mmol), 4-(2,6-diphenyl-4H-selenopyran-4-ylidene)acetaldehyde (0.155 g, 0.459 mmol) and Ac2O (3.0 ml) were combined in a round-bottom flask and heated at 105 °C for 10 min. The reaction was cooled to ambient temperature, precipitated with ether and the collected solid recrystallized from CH3CN/ether to yield 0.278 g (86%) of a golden-green solid: 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD2Cl2) δ 8.59 (t, 1 H, J=13.5 Hz), 8.40–7.80 (br s, 4 H), 7.71 (d, 8 H, J=7.0 Hz), 7.63-7.59 (m, 12 H), 6.85 (d, 2 H, J=13.0 Hz); analytically calculated for C37H27Se2·PF6: C, 57.38; H, 3.51; F, 14.72. Found: C, 57.34; H, 3.48; F, 14.76; LRMS (ESI) m/z 631.2 (calculated for C37H2780Se2: 631.0); λmax (CH2Cl2)=806 nm, ε=2.5 × 105 M−1 cm−1.

ClO4− 4-Methyl-2,6-di(phenyl)selenopyrylium perchlorate (50.0 mg, 0.122 mol), 4-(2,6-diphenyl-4H-selenopyran-4-ylidene)acetaldehyde (81.4 mg, 0.241 mmol) and Ac2O (2.0 ml) were treated as described for the PF6− salt to yield 82.0 mg (90%) of a golden-green solid: 1H NMR (500 MHz, 1:1 CD2Cl2:CD3OD) δ 8.77 (t, 1 H, J=13.5 Hz), 8.60–7.80 (m, 4 H), 7.71 (d, 8 H, J=7.0 Hz), 7.66–7.54 (m, 12 H), 6.83 (d, 2 H, J=14.0 Hz); analytically calculated for C37H27Se2·ClO4: C, 60.96; H, 3.73. Found: C, 60.69; H, 3.83; λmax (CH2Cl2)=806 nm, ε=2.5 × 105 M−1 cm−1.

Cl− The hexafluorophosphate salt (50 mg) was converted to the chloride salt by treating with Amberlite IRA-400 chloride form (200 mg) in a 1:1 CH2Cl2:MeOH mixture (3.0 ml). This process was repeated two more times after which the product was dissolved in CH2Cl2, washed with water, the organic layer dried with Na2SO4, filtered over Celite and after concentration recrystallized from CH3CN/ether to yield a bronze solid: 1H NMR (500 MHz, 3:1 CD3OD:CD2Cl2) δ 8.87 (t, 1 H, J=13.0 Hz), 8.40–7.80 (m, 4 H), 7.70 (d, 8 H, J=7.0 Hz), 7.56-7.50 (m, 12 H), 6.84 (d, 2 H, J=13.0 Hz); analytically calculated for C37H27Se2·Cl·4/3H2O: C, 64.50; H, 4.34; Cl, 5.15. Found: C, 64.54; H, 4.42; Cl, 4.98; λmax (CH2Cl2)=806 nm, ε=2.3 × 105 M−1 cm−1.

Br− The hexafluorophosphate salt (50 mg) was converted to the bromide salt by treating with Amberlite IRA-400 bromide form (200 mg) in a 1:1 CH2Cl2:MeOH mixture (3.0 ml). This process was repeated two more times after which the product was dissolved in CH2Cl2, washed with water, the organic layer dried with Na2SO4, filtered over Celite and after concentration recrystallized from CH3CN/ether to yield a bronze solid: 1H NMR (500 MHz, 3:2 CD2Cl2:CD3OD) δ 8.79 (t, 1 H, J=13.5 Hz), 8.40–7.80 (br s, 4 H), 7.71 (d, 8 H, J=7.0 Hz), 7.60–7.54 (m, 12 H), 8.50 (d, 2 H, J=13.0 Hz); analytically calculated for C37H27Se2·Br·H2O: C, 61.09; H, 4.02; Br, 10.98. Found: C, 61.08; H, 3.89; Br, 10.77; λmax (CH2Cl2)=806 nm, ε=2.3 × 105 M−1 cm−1.

Preparation of 4-(3-(2,6-diphenyl-4H-thiopyran-4-ylidene)prop-1-enyl)-2,6-diphenylselenopyrylium hexafluorophosphate ( 1b ) (CAS Registry Number: 79054-92-5). 4-Methyl-2,6-di(phenyl)thiopyrylium hexafluorophosphate (0.128 g, 0.312 mmol), 4-(2,6-diphenyl-4H-selenopyran-4-ylidene)acetaldehyde (0.157 g, 0.344 mmol) and Ac2O (2.0 ml) were combined in a round-bottom flask and heated at 105 °C for 10 min. The reaction was cooled to ambient temperature, CH3CN (2.0 ml) was added and ether was used to precipitate product from solution to yield 0.196 g (86%) of a copper–bronze solid: 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD2Cl2) δ 8.54 (t, 1 H, J=13.0 Hz), 8.20-7.80 (br s, 4 H), 7.78 (d, 4 H, J=8.0 Hz), 7.70 (d, 4 H, J=7.5 Hz), 7.66–7.58 (m, 12 H), 6.78 (d, 2 H, J=13.5 Hz); analytically calculated for C39H34O3Se2·PF6: C, 61.08; H, 3.74. Found: C, 61.10; H, 3.68; LRMS (ESI) m/z 583.3 (calculated for C37H27S80Se: 583.1); λmax (CH2Cl2)=784 nm, ε=2.0 × 105 M−1 cm−1.

Preparation of 4-(3-(2,6-dithiophen-2-yl-4H-thiopyran-4-ylidene)prop-1-enyl)-2,6-diphenylselenopyrylium ( 2a). 4-Methyl-2,6-di(phenyl)selenopyrylium hexafluorophosphate (0.102 g, 0.225 mmol), 4-(2,6-(thiophen-2-yl)-4H-thiopyran-4-ylidene)acetaldehyde (75.0 mg, 0.248 mmol) and Ac2O (3.0 ml) were combined in a round-bottom flask and heated at 105 °C for 5 min. The reaction was cooled to ambient temperature, precipitated with ether and the collected solid recrystallized from CH3CN/ether to yield 0.145 g (87%) of a bronze solid, mp 229–231 °C: 1H NMR [500 MHz, CD2Cl2] δ 8.46 (t, 1 H, J=13.0 Hz), 7.71–7.58 (m, 18 H), 7.26 (t, 2 H, J=4.0 Hz), 6.77 (d, 1 H, J=13.0 Hz), 6.70 (d, 1 H, J=14.0 Hz); analytically calculated for C33H23S3Se·PF6: C, 53.59; H, 3.13; F, 15.41. Found: C, 53.79; H, 3.13; F, 15.19; HRMS (ESI) m/z 595.0125(calculated for C33H23S380Se: 595.0122); λmax (CH2Cl2)=810 nm, ε=2.5 × 105 M−1 cm−1.

Preparation of 4-(3-(2,6-dithiophen-2-yl-4H-thiopyran-4-ylidene)prop-1-enyl)-2,6-diphenylthiopyrylium hexafluorophosphate ( 2b). 4-Methyl-2,6-diphenylthiopyrylium hexafluorophosphate (30.0 mg, 73.0 μmol), 4-(2,6-(thiophen-2-yl)-4H-thiopyran-4-ylidene)acetaldehyde (24.4 mg, 81.0 μmol) and Ac2O (1.0 ml) were combined in a round-bottom flask and heated at 105 °C for 5 min. The reaction was cooled to ambient temperature, CH3CN (4.0 ml) was added and ether was used to precipitate product from solution to yield 45.0 mg (88%) of a bronze solid, mp>260 °C: 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD2Cl2) δ 8.44 (t, 1 H, J=13.0 Hz), 8.40–7.80 (br s, 4 H), 7.78 (d, 4 H, J=7.0 Hz), 7.67–7.59 (m, 10 H), 7.24 (t, 2 H, J=4.5 Hz), 6.71 (d, 1 H, J=13.0 Hz), 6.63 (d, 1 H, J=13.5 Hz); analytically calculated for C33H23S4·PF6: C, 57.21; H, 3.35. Found: C, 56.97; H, 3.36; HRMS (ESI) m/z 547.0674 (calculated for C33H23S4: 547.0677); λmax (CH2Cl2)=789 nm, ε=2.2 × 105 M−1 cm−1.

Preparation of 4-(3-(2,6-dithiophen-2-yl-4H-thiopyran-4-ylidene)prop-1-enyl)-(2,6- dithiophen-2-yl)thiopyrylium hexafluorophosphate ( 3 ) (CAS Registry Number: 95410-36-9). 4-Methyl-2,6-di(thiophen-2-yl)thiopyrylium hexafluorophosphate (11.0 mg, 26.2 μmol), 4-(2,6-(thiophen-2-yl)-4H-thiopyran-4-ylidene)acetaldehyde (9.5 mg, 31.4 μmol) and Ac2O (1.0 ml) were combined in a round-bottom flask and heated at 105 °C for 5 min. The reaction was cooled to ambient temperature, CH2Cl2 (2.0 ml) was added and ether was used to precipitate product from solution to yield 17.8 mg (94%) of a bronze solid, mp>260 °C: 1H NMR (500 MHz, CD3CN) δ 8.32 (t, 1 H, J=13.5 Hz), 7.68 (d, 2 H, J=4 Hz), 7.56 (br. s, 4 H) 7.14 (t, 4 H, J=4.5 Hz), 6.48 (d, 2 H, J=13.0 Hz); analytically calculated for C29H19S6·PF6: C, 49.42; H, 2.72. Found: C, 49.19; H, 2.79; HRMS (ESI) m/z 558.9805 (calculated for C29H19S6: 558.9806); λmax (CH2Cl2)=813 nm, ε=2.8 × 105 M−1 cm−1. Spectral data agree with published spectra43.

SERRS nanoprobe synthesis

Gold nanoparticles were synthesized by adding 7.5 ml 1% (w/v) sodium citrate to 1.0 l boiling 0.25 mM HAuCl4. The as-synthesized gold nanoparticles were concentrated by centrifugation (10 min, 7,500 × g, 4 °C) and dialysed overnight (3.5 kDa MWCO; 5 l 18.2 MΩ cm). The dialysed gold nanoparticles (100 μl; 2.0 nM) were added to 1,000 μl absolute ethanol in the presence of 30 μl 99.999% tetraethyl orthosilicate (Sigma Aldrich), 15 μl 28% (v/v) ammonium hydroxide (Sigma Aldrich) and 1 μl CP dye (1−10 mM) in DMF. After shaking (375 rpm) for 25 min at ambient conditions in a plastic container, the SERRS nanoprobes were collected by centrifugation, washed with ethanol and redispersed in water to yield 2.0 nM SERRS nanoprobes.

SERRS nanoprobe characterization

The as-synthesized SERRS nanoprobes were characterized by transmission electron microscopy (TEM; JEOL 1200ex-II, 80 kV, 150,000 × magnification) to study the SERRS nanoprobe structural morphology. The size and concentration of the SERRS nanoprobes were determined on a Nanoparticle Tracking Analyzer (Malvern Instruments, Malvern, UK). Absorption spectra to determine possible nanoparticle aggregation (typically detectable at wavelengths>600 nm) were measured on an M1000Pro spectrophotometer (Tecan Systems Inc., San Jose, CA). Finally Raman spectra were acquired on a Renishaw InVIA system equipped with a 785-nm laser (Renishaw Inc., Hoffman Estates, IL). All measurements were performed at a laser power of 50 μW (1.0 s acquisition time, 5 × objective).

SERRS nanoprobe limit of detection

SERRS nanoprobes were synthesized as described above in the presence of an equimolar (1.0 μM) amount of 3 or IR792. SERRS imaging to determine the limit of detection was performed at 100 mW (2.0 s acquisition time (StreamLine), 5 × objective) on a phantom that consisted of a serially diluted IR792- or CP dye 3-based SERRS nanoprobe redispersed in 10 μl water (concentration range 3,000−0.003 fM; n=3). The Raman maps were generated using WiRE 3.4 software (Renishaw) by applying a DCLS algorithm. The Raman images were analysed with ImageJ software and plotted in GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software Inc., La Jolla, CA).

Animal studies

All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

In vivo comparison of EGFR-targeted 3- or IR792-SERRS nanoprobes

Eight-to-ten week-old female athymic nude mice (n=5; Hsd:Athymic Nude-Foxn1nu; Harlan Laboratories) were subcutaneously inoculated with the EGFR-overexpressing cell line A431 (1 × 106 cells; ATCC CRL-1555). After 2 weeks, the mice were injected with an equimolar amount (15 fmol g−1) of EGFR-targeted IR792- and 3-based SERRS nanoprobes. The EGFR-targeted SERRS nanoprobes were synthesized as described above in the presence of an equimolar (1.0 μM) amount of 3 or IR792. The as-synthesized SERRS nanoprobes were subsequently functionalized with sulfhydryl groups by heating the SERRS nanoprobes in 5 ml 2% (v/v) mercaptotrimethoxysilane in ethanol at 70 °C for 2 h. The sulfhydryl-functionalized SERRS nanoprobes were washed with water, redispersed in 10 mM MES buffer (pH 7.1), and conjugated to an EGFR-targeting antibody (cetuximab; Genentech, South San Francisco, CA) with a 4,000 Da heterobifunctional maleimide/N-hydroxysuccinimide polyethylene glycol linker44. Eighteen hours later, the mice were sacrificed by CO2 asphyxiation. The tumour was exposed and scanned by Raman imaging (10 mW, 1.5 s acquisition time (StreamLine), 5 × objective). The Raman maps were generated using WiRE 3.4 software (Renishaw) by applying a DCLS algorithm.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Harmsen, S. et al. Rational design of a chalcogenopyrylium-based surface-enhanced resonance Raman scattering-nanoprobe with attomolar sensitivity. Nat. Commun. 6:6570 doi: 10.1038/ncomms7570 (2015).

References

Wang, Y., Yan, B. & Chen, L. SERS tags: novel optical nanoprobes for bioanalysis. Chem. Rev. 113, 1391–1428 (2013) .

Kircher, M. F. et al. A brain tumor molecular imaging strategy using a new triple-modality MRI-photoacoustic-Raman nanoparticle. Nat. Med. 18, 829–834 (2012) .

Qian, X. et al. In vivo tumor targeting and spectroscopic detection with surface-enhanced Raman nanoparticle tags. Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 83–90 (2008) .

Kneipp, K. et al. Single molecule detection using surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS). Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 1667–1670 (1997) .

Nie, S. & Emory, S. R. Probing single molecules and single nanoparticles by surface-enhanced Raman scattering. Science 275, 1102–1106 (1997) .

Jeanmaire, D. L. & Van Duyne, R. P. Surface Raman spectroelectrochemistry. Part I. Heterocyclic, aromatic, and aliphatic amines adsorbed on the anodized silver electrode. J. Electroanal. Chem. Interfacial Electrochem. 84, 1–20 (1977) .

Zavaleta, C. L. et al. Multiplexed imaging of surface enhanced Raman scattering nanotags in living mice using noninvasive Raman spectroscopy. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 13511–13516 (2009) .

Faulds, K., Jarvis, R., Smith, W. E., Graham, D. & Goodacre, R. Multiplexed detection of six labeled oligonucleotides using surface enhanced resonance Raman scattering (SERRS). Analyst 133, 1505–1512 (2008) .

Gellner, M., Koempe, K. & Schluecker, S. Multiplexing with SERS labels using mixed SAMs of Raman reporter molecules. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 394, 1839–1844 (2009) .

Craig, D. et al. Confocal SERS mapping of glycan expression for the identification of cancerous cells. Anal. Chem. 86, 4775–4782 (2014) .

Gracie, K. et al. Simultaneous detection and quantification of three bacterial meningitis pathogens by SERS. Chem. Sci. 5, 1030–1040 (2014) .

McAughtrie, S., Lau, K., Faulds, K. & Graham, D. 3D optical imaging of multiple SERS nanotags in cells. Chem. Sci. 4, 3566–3572 (2013) .

Sha, M. Y., Xu, H., Natan, M. J. & Cromer, R. Surface-enhanced Raman scattering tags for rapid and homogeneous detection of circulating tumor cells in the presence of human whole blood. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 17214–17215 (2008) .

Cao, Y. C., Jin, R. & Mirkin, C. A. Nanoparticles with Raman spectroscopic fingerprints for DNA and RNA detection. Science 297, 1536–1540 (2002) .

Yuen, J. M., Shah, N. C., Walsh, J. T. Jr., Glucksberg, M. R. & Van Duyne, R. P. Transcutaneous glucose sensing by surface-enhanced spatially offset Raman spectroscopy in a rat model. Anal. Chem. 82, 8382–8385 (2010) .

McQueenie, R. et al. Detection of inflammation in vivo by surface-enhanced Raman scattering provides higher sensitivity than conventional fluorescence imaging. Anal. Chem. 84, 5968–5975 (2012) .

Graham, D., Mallinder, B. J., Whitcombe, D. & Smith, W. E. Surface enhanced resonance Raman scattering (SERRS) - a first example of its use in multiplex genotyping. Chemphyschem 2, 746–748 (2001) .

Hildebrandt, P. & Stockburger, M. Surface-enhanced resonance Raman spectroscopy of Rhodamine 6G adsorbed on colloidal silver. J. Phys. Chem. 88, 5935–5944 (1984) .

Dieringer, J. A. et al. Surface-enhanced Raman excitation spectroscopy of a single rhodamine 6G molecule. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 849–854 (2009) .

Harmsen, S. et al. Surface-enhanced resonance Raman scattering nanostars for high-precision cancer imaging. Sci. Transl. Med. 7, 271ra277 (2015) .

Samanta, A. et al. Ultrasensitive near-infrared Raman reporters for SERS-based in vivo cancer detection. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 50, 6089–6092 (2011) .

Detty, M. R. & Murray, B. J. Telluropyrylium dyes. 1. 2,6-Diphenyltelluropyrylium dyes. J. Org. Chem. 47, 5235–5239 (1982) .

Stiles, P. L., Dieringer, J. A., Shah, N. C. & Van Duyne, R. P. Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Annu. Rev. Anal. Chem. 1, 601–626 (2008) .

Detty, M. R. et al. Electron transport in 4H-1,1-dioxo-4-(dicyanomethylidene)thiopyrans. Investigation of x-ray structures of neutral molecules, electrochemical reduction to the anion radicals, and absorption properties and epr spectra of the anion radicals. J. Org. Chem. 60, 1674–1685 (1995) .

Leonard, K., Nelen, M., Raghu, M. & Detty, M. R. Chalcogenopyranones from disodium chalcogenide additions to 1,4-pentadiyn-3-ones. The role of enol ethers as intermediates. J. Heterocycl. Chem. 36, 707–717 (1999) .

Detty, M. R., McKelvey, J. M. & Luss, H. R. Tellurapyrylium dyes. 2. The electron-donating properties of the chalcogen atoms to the chalcogenapyrylium nuclei and their radical dications, neutral radicals, and anions. Organometallics 7, 1131–1147 (1988) .

Panda, J., Virkler, P. R. & Detty, M. R. A comparison of linear optical properties and redox properties in chalcogenopyrylium dyes bearing ortho-substituted aryl substituents and tert-butyl substituents. J. Org. Chem. 68, 1804–1809 (2003) .

Stoeber, W., Fink, A. & Bohn, E. Controlled growth of monodisperse silica spheres in the micron size range. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 26, 62–69 (1968) .

Liz-Marzán, L. M., Giersig, M. & Mulvaney, P. Synthesis of nanosized gold−silica core−shell particles. Langmuir 12, 4329–4335 (1996) .

Mulvaney, S. P., Musick, M. D., Keating, C. D. & Natan, M. J. Glass-coated, analyte-tagged nanoparticles: a new tagging system based on detection with surface-enhanced Raman scattering. Langmuir 19, 4784–4790 (2003) .

Bouit, P.-A. et al. A "cyanine-cyanine" salt exhibiting photovoltaic properties. Org. Lett. 11, 4806–4809 (2009) .

Detty, M. R., Merkel, P. B., Hilf, R., Gibson, S. L. & Powers, S. K. Chalcogenapyrylium dyes as photochemotherapeutic agents. 2. Tumor uptake, mitochondrial targeting, and singlet-oxygen-induced inhibition of cytochrome c oxidase. J. Med. Chem. 33, 1108–1116 (1990) .

Haekkinen, H. The gold-sulfur interface at the nanoscale. Nat. Chem. 4, 443–455 (2012) .

Mahajan, S., Baumberg, J. J., Russell, A. E. & Bartlett, P. N. Reproducible SERRS from structured gold surfaces. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 9, 6016–6020 (2007) .

von Maltzahn, G. et al. SERS-coded gold nanorods as a multifunctional platform for densely multiplexed near-infrared imaging and photothermal heating. Adv. Mater. 21, 3175–3180 (2009) .

Detty, M. R. & Merkel, P. B. Chalcogenapyrylium dyes as potential photochemotherapeutic agents. Solution studies of heavy atom effects on triplet yields, quantum efficiencies of singlet oxygen generation, rates of reaction with singlet oxygen, and emission quantum yields. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 112, 3845–3855 (1990) .

Dulkeith, E. et al. Gold nanoparticles quench fluorescence by phase induced radiative rate suppression. Nano Lett. 5, 585–589 (2005) .

Thakor, A. S. et al. The fate and toxicity of Raman-active silica-gold nanoparticles in mice. Sci. Transl. Med. 3, 79ra33 (2011) .

Jokerst, J. V., Cole, A. J., Van de Sompel, D. & Gambhir, S. S. Gold nanorods for ovarian cancer detection with photoacoustic imaging and resection guidance via Raman imaging in living mice. ACS Nano 6, 10366–10377 (2012) .

Freeman, R. G., Bright, R. M., Hommer, M. B. & Natan, M. J. Size selection of colloidal gold aggregates by filtration: effect on surface-enhanced Raman scattering intensities. J. Raman Spectrosc. 30, 733–738 (1999) .

Grochala, W., Kudelski, A. & Bukowska, J. Anion-induced charge-transfer enhancement in SERS and SERRS spectra of Rhodamine 6G on a silver electrode: how important is it? J. Raman Spectrosc. 29, 681 (1998) .

Yuan, H. et al. Quantitative surface-enhanced resonant Raman scattering multiplexing of biocompatible gold nanostars for in vitro and ex vivo detection. Anal. Chem. 85, 208–212 (2013) .

Kudinova, M. A., Kurdyukov, V. V., Kachkovski, A. V. & Tolmachev, A. I. Pyrylocyanines. 36. alpha-Thienyl-substituted pyrylo- and thiopyrylocyanines. Khim Geterotsikl 494–500 (1998) .

Chung, E. et al. Use of surface-enhanced Raman scattering to quantify EGFR markers uninhibited by cetuximab antibodies. Biosens. Bioelectron. 60, 358–365 (2014) .

Acknowledgements

We thank the Electron Microscopy and Molecular Cytology Core Facility at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC). This work was supported in part by the following grants: NIH R01 EB017748 (M.F.K.); NIH K08 CA163961 (M.F.K.); M.F.K. is a Damon Runyon–Rachleff Innovator supported (in part) by the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation (DRR-29-14); MSKCC Center for Experimental Therapeutics Grant (M.F.K.). MSKCC Center for Molecular Imaging and Nanotechnology Grant (M.F.K.); MSKCC Technology Development Fund Grant (M.F.K.); Geoffrey Beene Cancer Research Center at MSKCC Grant Award (M.F.K.) and Shared Resources Award (M.F.K.); The Dana Foundation Brain and Immuno-Imaging Grant (M.F.K.); Dana Neuroscience Scholar Award (M.F.K.); Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals/RSNA Research Scholar Grant (M.F.K.); MSKCC Brain Tumor Center Grant (M.F.K.); Society of MSKCC Research Grant (M.F.K.); NIH GM-94367 (M.R.D.); and the National Science Foundation (CHE-1151379, M.R.D.). M.A.W. is supported by a National Science Foundation Integrative Graduate Education and Research Traineeship Grant (NSF, IGERT 0965983 at Hunter College). Acknowledgements are also extended to the grant-funding support provided by the MSKCC Core Grant (P30 CA008748).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.H. and M.A.B. performed the experiments, analysed the data and wrote the paper. M.A.W. and R.H. participated in performing the experiments. M.F.K. and M.R.D. supervised the study, advised on experimental design, analysed the data and edited the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Figures 1-6, Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Methods (PDF 1029 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Harmsen, S., Bedics, M., Wall, M. et al. Rational design of a chalcogenopyrylium-based surface-enhanced resonance Raman scattering nanoprobe with attomolar sensitivity. Nat Commun 6, 6570 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7570

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms7570

This article is cited by

-

Nanomaterial-based contrast agents

Nature Reviews Methods Primers (2023)

-

Multiplexed imaging in oncology

Nature Biomedical Engineering (2022)

-

DNA-enabled rational design of fluorescence-Raman bimodal nanoprobes for cancer imaging and therapy

Nature Communications (2019)

-

Delineating the tumor margin with intraoperative surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy

Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry (2019)

-

Cancer imaging using surface-enhanced resonance Raman scattering nanoparticles

Nature Protocols (2017)

Comments

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines. If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.