Abstract

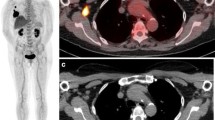

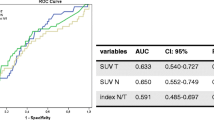

We have compared 2-deoxy-2-[18F]-fluoro-d-glucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) images of large or locally advanced breast cancers (LABC) acquired during Anthracycline-based chemotherapy. The purpose was to determine whether there is an optimal method for defining tumour volume and an optimal imaging time for predicting pathologic chemotherapy response. Method: PET data were acquired before the first and second cycles, at the midpoint and at the endpoint of neoadjuvant chemotherapy. FDG uptake was quantified using the mean and maximum standardized uptake values (SUV) and the coefficient of variation within a region of interest. Receiver-operator characteristic (ROC) analysis was used to determine the discrimination between tumours demonstrating a high pathological response (i.e. those with greater than 90% reduction in viable tumour cells) and low pathological response. Results: Only tumours with an initial tumour to background ratio (TBR) of greater than five showed a difference between response categories. In terms of response discrimination, there was no statistically significant advantage of any of the methods used for image quantification or any of the time points. The best discrimination was measured for mean SUV at the midpoint of therapy, which identified 77% of low responding tumours whilst correctly identifying 100% of high responding tumours and had an ROC area of 0.93. Conclusion: FDG-PET is efficacious for predicting the pathologic response of most primary breast tumours throughout the duration of a neoadjuvant chemotherapy regimen. However, this technique is ineffective for tumours with low image contrast on pre-therapy PET scans.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

von Minckwitz G, Costa SD, Eirmann W et al (1999) Maximized reduction of primary breast tumour size using preoperative chemotherapy with doxorubicin and docetaxel. J Clin Oncol 7:1999–2005

Heys SD, Sarkar TK, Hutcheon AW (2004) Docetaxel as adjuvant and neoadjuvant treatment for patients with breast cancer. Expert Opin Pharmacol 5:2147–2157

Ogston KN, Miller ID, Payne S et al (2003) A new histological grading system to assess response of breast cancers to primary chemotherapy: prognostic significance and survival. Breast 12:320–327

Fornage BD, Toubas O, Morel M (1987) Clinical, mammographic, and sonographic determination of preoperative breast cancer size. Cancer 60:765–771

Vinnicombe SJ, MacVicar AD, Guy RL et al (1996) Primary breast cancer: mammographic changes after neo-adjuvant chemotherapy, with pathologic correlation. Radiology 198:333–340

Smith IC, Welch AE, Hutcheon AW et al (2000) Positron emission tomography using [18F]-fluorodeoxy-D-glucose to predict the pathologic response of breast cancer to primary chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 18:1676–1688

Schelling M, Avril N, Nahrig J et al (2000) Positron emission tomography using [(18)F]fluorodeoxyglucose for monitoring primary chemotherapy in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol 18:1689–1695

Mankoff DA, Dunnwald LK, Gralow JR et al (2003) Changes in blood flow and metabolism in locally advanced breast cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J␣Nucl Med 44:1806–1814

Kim SJ, Kim SK, Lee ES et al (2004) Predictive value of [18F]FDG PET for pathologic response of breast cancer to neo-adjuvant chemotherapy. Ann Oncol 15:1352–1357

van de Wiele C, Dierckx R, Scopinaro F et al (2002) Nuclear medicine imaging for prediction or early assessment of response to chemotherapy in patients suffering from breast carcinoma. Breast Cancer Res Treat 72:279–286

Bombardieri E, Aktolun C, Baum RP et al (2003) FDG-PET: procedure guidelines for tumour imaging. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 30:BP115–BP124

Stahl A, Ott K, Schwaiger M et al (2004) Comparison of different SUV-based methods for monitoring cytotoxic therapy with FDG-PET. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 31:1471–1478

Krak NC, Boellaard R, Hoekstra OS et al (2005) Effects of ROI definition and reconstruction method on quantitative outcome and applicability in a response monitoring trial. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 32:294–301

Vranjesevic D, Schiepers C, Silverman DH et al (2003) Relationship between 18F-FDG uptake and breast density in women with normal breast tissue. J Nucl Med 44:1238–1242

Erdi YE, Mawlawi O, Larson SM et al (1997) Segmentation of lung lesion volume by adaptive positron emission tomography image thresholding. Cancer 80:2505–2509

Zasadny KR, Kison PV, Francis IR et al (1998) FDG-PET determination of metabolically active tumour volume and comparison with CT. Clin Positron Imaging 1:123–129

O’Sullivan F, Roy S, Eary J (2003) A statistical measure of tissue heterogeneity with application to 3D PET sarcoma data. Biostatistics 4:433–448

Freedman NMT, Sundaram SK, Kurdziel K et al (2003) Comparison of SUV and Patlak slope for monitoring of cancer therapy using serial PET scans. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 30:46–53

Sundaram SK, Freedman NMT, Carrasquillo JA et al (2004) Simplified kinetic analysis of tumor 18F-FDG uptake: a dynamic approach. J Nucl Med 45:1328–1333

Freedman RJ, Aziz N, Albanes D et al (2004) Weight and body composition changes during and after adjuvant chemotherapy in women with breast cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89:2248–2253

Bland M (1992) An introduction to medical statistics. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, pp 217–224

Kairisto V, Poola A (1995) Software for illustrative presentation of basic clinical characteristics of laboratory tests – GraphROC for Windows. Scand J Clin Lab Invest 55:43–60

Bland M (1992) An introduction to medical statistics. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, pp 255–258

Black QC, Grills IS, Kestin LL et al (2004) Defining a radiotherapy target with positron emission tomography. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 60:1272–1282

Nestle U, Kremp S, Schaefer-Schuler A et al (2005) Comparison of different methods for delineation of 18F-FDG PET-positive tissue for target volume definition in radiotherapy of patients with non-small cell lung cancer. J Nucl Med 46:1342–1348

Daisne JF, Sibomana M, Bol A et al (2003) Tri-dimensional automatic segmentation of PET volumes based on measured source-to-background ratios: influence of reconstruction algorithms. Radiother Oncol 69:247–250

Krak NC, van der Hoeven JJM, Hoekstra OS et al (2003) Measuring [18F]FDG uptake in breast cancer during chemotherapy: comparison of analytical methods. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 30:674–681

Boellaard R, Krak NC, Hoekstra OS et al (2004) Effects of noise, image resolution, and ROI definition on the accuracy of standardised uptake values: a simulation study. J Nucl Med 45:1519–1527

Zu XL, Guppy M (2004) Cancer metabolism: facts, fantasy and fiction. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 313:459–465

Wieder HA, Brücher BLDM, Zimmermann F et al (2004) Time course of tumor metabolic activity during chemoradiotherapy of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and response to treatment. J Clin Oncol 22:900–908

Avril N, Sassen S, Schmalfeldt B et al (2005) Prediction of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy by sequential F-18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in patients with advanced-stage ovarian cancer. J Clin Oncol 23:7445–7453

Montemurro F, Martincich L, De Rosa G et al (2005) Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI and sonography in patients receiving primary chemotherapy for breast cancer. Eur Radiol 15:1224–1233

Stockler M, Wilcken N, Ghersi D et al (2000) Systematic reviews of systematic therapy for advanced breast cancer. Cancer Treat Rev 26:151–168

Fumoleau P, Kerbrat P, Romestaing P et al (2003) Randomized trial comparing six versus three cycles of epirubicin-based adjuvant chemotherapy in premenopausal, node-positive breast cancer patients: 10-year follow-up results of the French Adjuvant Study Group 01 trial. J Clin Oncol 21:298–305

Cleator S, Parton M, Dowsett M (2002) The biology of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer 9:183–195

Arpino G, Ciocca DR, Weiss H et al (2005) Predictive value of apoptosis, proliferation, HER-2, and topoisomerase IIα for anthracycline chemotherapy in locally advanced breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 92:69–75

Takei T, Kuge Y, Zhao S et al (2005) Enhanced apoptotic reaction correlates with suppressed tumor glucose utilization after cytotoxic chemotherapy: Use of 99mTc-Annexin V, 18F-FDG, and histologic evaluation. J Nucl Med 46:794–799

Ambudkar SV, Dey S, Hrycyna CA et al (1999) Biochemical, cellular and pharmacological aspects of the multidrug transporter. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 39:361–398

Su FX, Hu XQ, Jia WJ et al (2003) Glutathion S Transferase π indicates chemotherapy resistance in breast cancer. J Surg Res 113:102–108

Burgman P, O’Donoghue JA, Humm JL et al (2001) Hypoxia induced increase in FDG uptake in MCF-7 cells. J␣Nucl Med 42:170–175

Harrison L, Blackwell K (2004) Hypoxia and anemia: factors in decreased sensitivity to radiation therapy and chemotherapy? Oncologist 9(suppl 5):S31–S40

Mahoney BP, Raghunand N, Baggett B et al (2003) Tumour acidity, ion trapping and chemotherapeutics I. Acid pH affects the distribution of chemotherapeutic agents in vitro. Biochem Pharmacol 66:1207–1218

Hayes C, Padhani AR, Leach MO (2002) Assessing changes in tumour vascular function using dynamic contrast- enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. NMR Biomed 15:154–163

Pickles MD, Lowry M, Manton DJ et al (2005) Role of dynamic contrast enhanced MRI in monitoring early response of locally advanced breast cancer to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat 91:1–10

Tseng J, Dunnwald LK, Schubert EK et al (2004) F-18-FDG kinetics in locally advanced breast cancer: correlation with tumor blood flow and changes in response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J Nucl Med 45:1829–1837

Kaushal V, Kaushal GP, Mehta P (2004) Differential toxicity of anthracyclines on cultured endothelial cells. Endothelium 11:253–258

Wakabayashi I, Groschner K (2003) Vascular actions of anthracycline antibiotics. Curr Med Chem 10:427–436

Spaepen K, Stroobants S, Dupont P et al (2003) [18F]FDG PET monitoring of tumour response to chemotherapy: does [18F]FDG uptake correlate with the viable tumour cell fraction? Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 30:682–688

Bos R, van der Hoeven JJM, van der Wall E et al (2002) Biologic correlates of 18Fluorodeoxyglucose uptake in human breast cancer measured by positron emission tomography. J Clin Oncol 20:379–387

Avril N, Rose CA, Schelling M et al (2000) Breast imaging with positron emission tomography and fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose: use and limitations. J Clin Oncol 18:3495–3502

Semple SIK, Gilbert FJ, Redpath TW et al (2003) Correlation of MRI-PET rim enhancement in breast cancer. A delivery related phenomenon with therapy implications? Lancet Oncol 4:759

Clarke H, Pallister CJ (2005) The impact of anaemia on outcome in cancer. Clin Lab Haem 27:1–13

Kralickova P, Melichar B, Malir F et al (2004) Renal tubular dysfunction and urinary zinc excretion in breast cancer patients treated with anthracycline-based combination chemotherapy. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 23:579–584

Kuerer HM, Newman LA, Buzdar AU et al (1998) Pathologic tumor response in the breast following neoadjuvant chemotherapy predicts axillary lymph node status. Cancer J␣Sci Am 4:230–236

Honkoop AH, van Diest PJ, de Jong JS et al (1998) Prognostic role of clinical, pathological and biological characteristics in patients with locally advanced breast cancer. Br J␣Cancer 77:621–626

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from Cancer Research UK. The first author was also supported by a studentship from the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council. The authors would like to thank Felice Chilcott and other members of the John Mallard Scottish PET Centre for their help in acquiring the data for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

McDermott, G.M., Welch, A., Staff, R.T. et al. Monitoring primary breast cancer throughout chemotherapy using FDG-PET. Breast Cancer Res Treat 102, 75–84 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-006-9316-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-006-9316-7