Abstract

Purpose

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) may cause a decreased apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) on diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging (DW MRI) and an increased standardized uptake value (SUV) on fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET/CT). We analysed the reproducibility of ADC and SUV measurements in HNSCC and evaluated whether these biomarkers are correlated or independent.

Methods

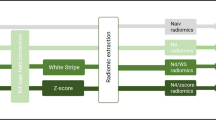

This retrospective analysis of DW MRI and FDG PET/CT data series included 34 HNSCC in 33 consecutive patients. Two experienced readers measured tumour ADC and SUV values independently. Statistical comparison and correlation with histopathology was done. Intra- and inter-observer agreement for ADC and SUV measurements was assessed.

Results

Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) analysis showed almost perfect reproducibility (>0.90) for ADCmean, ADCmin, SUVmax and SUVmean values for intra-observer and inter-observer agreement. Mean ADCmean and ADCmin in HNSCC were 1.05 ± 0.34 × 10−3 mm2/s and 0.65 ± 0.29 × 10−3 mm2/s, respectively. Mean SUVmean and mean SUVmax were 7.61 ± 3.87 and 12.8 ± 5.0, respectively. Although statistically not significant, a trend towards higher SUV and lower ADC was observed with increasing tumour dedifferentiation. Pearson’s correlation analysis showed no significant correlation between ADC and SUV measurements (r −0.103, −0.051; p 0.552, 0.777).

Conclusion

Our data suggest that ADC and SUV values are reproducible and independent biomarkers in HNSCC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Over 90 % of malignant head and neck tumours in adults are squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCC) [1]. Appropriate assessment of superficial and deep tumour spread, regional lymphadenopathy and distant metastases is essential for staging and therapeutic planning. According to the guidelines of the International Union Against Cancer (UICC) and American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), tumour staging requires endoscopy with biopsy and additional imaging [1].

Morphologic evaluation is preferably done with contrast-enhanced CT or MRI. However, fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET/CT) and diffusion-weighted MR imaging (DW MRI) are increasingly used in oncologic head and neck imaging in order to add diagnostic information beyond morphology [2, 3]. Although each modality is based on different physical principles, both modalities may be seen as functional imaging tools as they allow interrogation of tissue with regard to certain biologic properties. FDG PET/CT measures increased cellular glucose metabolism as expressed by the standardized uptake value (SUV). In oncologic imaging, increased SUV may be seen as a sign of increased cell proliferation [1–4] and may also correlate with the degree of tumour necrosis [5]. The principle of DW MRI as a functional biomarker is based on the assessment of random (Brownian) motion of extracellular water molecules, which is restricted in hypercellular tumour tissue, as expressed by the decreased apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) value. In addition, ADC values may also reflect cell proliferation [6, 7] and may be affected by the presence of tumour necrosis [8]. Based on previous studies it appears that most HNSCC have lower ADC values than normal tissue because of their higher cellular density [8].

Since both increased SUV and decreased ADC values are seen in the context of neoplasia although they refer to different biologic phenomena, it would be of interest to know whether these parameters are statistically correlated or independent in order to facilitate their use in diagnostic interpretation. Previous studies in different tumour types have found diverging results. An inverse correlation was recently demonstrated between SUV and ADC values in gastrointestinal stromal tumours [9], lung cancer [10] and in cervical cancer [11], whereas no correlation was found in lymphoma [12]. To the best of our knowledge, only three reports have so far compared SUV and ADC values in HNSCC. The results were diverging with either significant correlation or no correlation [13–15]. It also remains open whether SUV and ADC measurements are reproducible in HNSCC due to the paucity of reported data [16, 17].

The purpose of the current study was to assess the reproducibility of ADC and SUV measurements in patients with biopsy-proven HNSCC and to evaluate whether ADC and SUV values are statistically correlated or independent functional parameters.

Materials and methods

Study design and patient selection

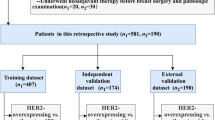

This retrospective study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee and was performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Helsinki II Declaration. Informed consent was waived. Inclusion criteria were: adult patients with histologically proven HNSCC, who had undergone whole-body FDG PET/CT and high-resolution head and neck DW MRI prior to treatment (mean delay between the two exams = 3.5 days) and who were subsequently treated with surgery, radio(chemo)therapy or a combination of the two. A computerized search of the PACS archives and medical records of our institution retrospectively identified 34 consecutive patients who fulfilled the above-mentioned inclusion criteria. One patient had to be excluded from the study because of poor DW MRI image quality due to metal implants causing major image distortion. Therefore, 33 patients formed the basis of the current study (22 men and 11 women with a mean age of 54.7 years; range 16–77 years). One patient had two synchronous HNSCC resulting in a total of 34 evaluated tumours. In 24 patients, the indication for imaging was primary staging of HNSCC; in 10 patients, the indication was follow-up or suspected recurrence 45 months (range 10–95 months) after surgery ± radiotherapy. Primary tumour sites were as follows: oropharynx (n = 13), hypopharynx (n = 6), oral cavity (n = 6), larynx (n = 3), nasopharynx (n = 3), parotid gland (n = 2) and paranasal sinuses (n = 1). Tumour size assessed by the longest diameter measured in the axial plane according to RECIST criteria was 32 ± 14 mm (range 15–64 mm). Of the tumours, 8 were poorly differentiated or undifferentiated, 21 were moderately differentiated and 5 were well differentiated. There were one T1, four T2, five T3 and fourteen T4 primary tumours and four T1, two T2, two T3 and two T4 recurrent tumours.

PET/CT acquisition

All PET/CT examinations were performed on an integrated PET/CT scanner (Biograph 16-slice PET/CT scanner, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany). Prior to the exam, all patients had fasted for at least 6 h and the measured intravenous serum glucose concentration prior to study initiation was less than 8.5 mmol/l. PET data acquisition was started 60 min after injection of 370 MBq of 18F-FDG with 3 min per bed position for a total of 7 to 9 beds, from the vertex to the proximal thigh. CT data acquisition for attenuation correction was performed using the following parameters: 120 kV, 180 mAs, 16 × 1.5 collimation, pitch = 1.2, 1 s per rotation. PET image reconstruction was done using an attenuation-weighted ordered subset expectation maximization (AWOSEM) iterative reconstruction algorithm with a matrix of 168 × 168 and a slice thickness of 5 mm. The reconstruction parameters were set to the default values (four iterations, eight subsets, and a post-processing Gaussian kernel with a full-width at half-maximum of 5 mm). The SUV was calculated by using the standard formula normalized by body weight: SUV = cdc/(di/w), where cdc is the decay-corrected tracer tissue concentration (Bq/g), di is the injected dose (Bq), and w is the patient’s body weight (g) [18]. In addition, high-resolution, contrast-enhanced CT, which is part of the routine PET/CT protocol for HNSCC in our institution, was obtained after intravenous administration of 2 ml/kg of iohexol (Accupaque 350®, GE Healthcare SA, Opfikon, Switzerland) in all patients.

MRI acquisition

The MRI examinations were performed with dedicated head and neck coils on a 1.5 T Espree machine (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) in 23 patients and on a 3 T Trio (Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) in 11 patients. The MRI protocol on both machines included axial T2-weighted, axial T1-weighted and axial diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) sequences obtained before intravenous injection of contrast material followed by an axial T1-weighted sequence after contrast material application (gadobenate dimeglumine, Multihance®, Bracco Diagnostics, Milan, Italy). Depending on tumour location, additional T1-weighted sequences with fat saturation were then obtained in the coronal and/or sagittal plane. DWI was performed using a single-shot echo planar technique with fat suppression on both machines (repetition time ms/echo time ms, TR/TE = 3,200/86 and TR/TE = 2,200/63, respectively, 40 sections, slice thickness = 5 mm, intersection gap = 1.5 mm, field of view = 230 × 230 mm, matrix = 128 × 128, 3 acquired signals, pixel resolution = 1.8 × 1.8 × 5.0 mm, acquisition time = 3 min 02 s and 3 min 17 s, respectively). Two b values were applied: 0 and 1,000 s/mm2. DWI images were acquired in three orthogonal directions and then combined into a single trace image. ADC maps were calculated automatically by the MRI software using the following formula: ADC (mm2/s) = -ln (S2/S1)/(b2-b1), with b1 = 0 and b2 = 1,000. The parameters for the fast spin echo T2- weighted sequence at 1.5 and 3 T were as follows: TR/TE = 3,300/106 and TR/TE = 3,010/82, respectively, 24 sections, slice thickness = 4 mm, intersection gap = 0.8 mm, field of view = 230 × 180 mm, matrix = 512 × 416, three acquired signals, pixel resolution = 0.4 × 0.4 × 4.0 mm, acquisition time = 3 min 30 s and 4 min 20 s, respectively). The fast spin echo T1-weighted sequences performed before and after intravenous injection of contrast material at 1.5 and 3 T had the following parameters: TR/TE = 771/11 and TR/TE = 687/9, respectively, 30 slices, slice thickness = 3 mm, intersection gap = 0.6 mm, field of view = 230 × 230 mm, matrix = 512 × 512, two acquired signals, pixel resolution = 0.4 × 0.4 × 4.0 mm, acquisition time = 3 min 56 s and 4 min 36 s, respectively). In order to obtain good MRI image quality, all patients were carefully instructed to refrain from vigorous swallowing or breathing during image acquisition, in particular during the acquisition of DWI sequences. Small breaks were made between individual sequences, so as to allow patients to clear the throat of mucous secretions, to cough and to swallow between the sequences.

Image evaluation, ADC and SUV measurements

All images were analysed by two independent readers who evaluated both data sets (MRI including DW MRI and PET/CT). One reader was a board-certified nuclear medicine specialist with additional expertise in head and neck MRI, and the second reader was a board-certified head and neck radiologist with additional expertise in PET/CT. Defined criteria were used for each modality and both readers were blinded to clinical data and histopathologic results. Image quality and lesion conspicuity on each modality were evaluated using a three-point scale (good-moderate-poor). Prior to performing measurements, each reader also assessed the presence or absence of geometric distortion, breathing and swallowing artefacts. All images were evaluated in the transverse plane on a PACS workstation to allow comparison between DW MRI acquired in the axial plane and PET/CT images.

First, the fused T2-weighted, b1000 images and the corresponding PET/CT fused images were identified and matched, so as to enable measurements at the same anatomic levels (Figs. 1 and 2). Then one reader drew a region of interest (ROI) manually avoiding negative pixels by contouring the tumour area identified on the fused T2-weighted, b1000 image and the respective ROI size was saved in a DICOM format. This ROI with a predefined size was then used for subsequent measurements on the anatomically corresponding ADC maps and PET images of the same patient. The size of the predefined ROI varied from 5 to 825 mm2 (mean = 199 mm2) depending on the size of the individual tumours on axial slices. In each head and neck tumour, the measurements were performed at the largest tumour size levels. The precise anatomic levels where the measurements were performed were recorded. In a first session, the first reader measured ADC and SUV values for each lesion. Then, the second reader measured the same parameters using the predefined ROI size and performing the measurements at the predefined anatomic levels. Two weeks later, measurements were repeated by the two readers, independently, using the same methodology, so as to obtain a second data set for each observer enabling assessment of intra-observer agreement.

Anatomically matched corresponding transverse slices of inverted b1000 (a), PET (b), fused T2-weighted, b1000 (c) and fused PET/CT (d) images of a 63-year-old male with primary squamous cell carcinoma of the hypopharynx staged T4a N2c M0. Both PET/CT and MRI fused images allow correct anatomic assessment of the hypopharyngeal lesion that invades the retrocricoarytenoid region and both piriform sinuses

Anatomically matched corresponding transverse slices of inverted b1000 (a), PET (b), fused T2-weighted, b1000 (c) and fused PET/CT (d) images of a 59-year-old patient with primary undifferentiated carcinoma of the nasopharynx staged T4 N3 M0. Both PET/CT and MRI fused images allow correct anatomic assessment of the right nasopharyngeal carcinoma that extends to the skull base, parapharyngeal and retropharyngeal space

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using a commercially available software program (SPSS software for Windows, version 11.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Two methods were used to assess intra- and inter-observer agreement for SUV and ADC measurements [19–21]. Inter- and intra-observer reproducibility of ADC and SUV of tumours were determined as mean absolute difference (bias) and as 95 % confidence interval (CI) of the mean difference (limits of agreement), according to the methods of Bland and Altman [19]. Relative bias (bias/mean value) and relative limits of agreement (limits of agreement/mean value) were calculated. Single measure intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) were calculated using the two-way random analysis of variance (ANOVA) on average measures (ICC ranges 0.00–1.00 with values closer to 1.00 representing better reproducibility) [19]. Interpretation of ICC was categorized according to Landis and Koch [20] as follows: <0, no reproducibility; 0.0–0.20, slight reproducibility; 0.21–0.40, fair reproducibility; 0.41–0.60, moderate reproducibility; 0.61–0.80, substantial reproducibility; and 0.81–1.00, almost perfect reproducibility. Pearson’s correlation coefficient analysis was used to evaluate the correlations between ADC (ADCmean, ADCmax, ADCmin) and SUV (SUVmean, SUVmax, SUVmin) values. A p value of less than 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Kruskal-Wallis one-way ANOVA [21] was used to detect any statistically significant difference between ADC and SUV values and ratios in primary versus recurrent tumours and in different histologic tumour grades. Student’s t test was used to compare significant difference between ADC at 1.5 and 3 T.

Results

Image quality and tumour detection

MRI image quality was considered as good in 20 patients (61 %) and moderate in 13 patients (39 %). DW MRI image quality did not depend on tumour location but on patient cooperation during the MRI examination. Susceptibility artefacts caused minor signal loss and minor to moderate geometric distortion on DWI images in 23 of the 33 patients (70 %); slight motion artefacts due to swallowing or breathing were present in 13 patients (39 %). Regarding the PET/CT, image quality was good in 27 cases (82 %) and moderate in 6 cases (18 %). Artefacts due to dental amalgam were seen in 14 patients (42 %) and swallowing/breathing artefacts were present in 2 cases (6 %).

Conspicuity of all 34 HNSCC was rated as good on all fused T2-weighted, b1000 images, ADC maps and PET/CT images. All tumours showed a restricted diffusion with high signal intensity on the b1000 images. Anatomic matching of the fused T2-weighted, b1000 images and PET/CT images was feasible in all tumours with comparable tumour conspicuity on both modalities (Figs. 1 and 2).

ADC and SUV values

Table 1 summarizes the results of ADC (ADCmean, ADCmin) and SUV (SUVmean, SUVmax) measurements of both observers performed during the two readings. The mean ADCmean and ADCmin values of all tumours together were 1.05 ± 0.34 × 10−3 mm2/s and 0.65 ± 0.29 × 10−3 mm2/s, respectively. The mean SUVmean and SUVmax values of all tumours were 9.86 ± 3.82 and 12.80 ± 5.00, respectively. SUVmax values were higher for primary than for recurrent tumours (p = 0.025), whereas no statistically significant difference was observed regarding SUVmean, ADCmean and ADCmin (p = 0.109, p = 0.897 and p = 0.257, respectively). There was no statistically significant difference for ADCmean values of HNSCC at 1.5 and 3 T (p = 0.201).

Intra- and inter-observer agreement

The mean bias and the limits of agreement for intra- and inter-observer measurements of SUV and ADC are displayed in the Bland–Altman plots of Figs. 3 and 4 and summarized in Tables 2 and 3. ICC showed almost perfect reproducibility for ADC and SUV values (Table 4).

Intra-observer reproducibility measurements in tumours of ADCmean (a), SUVmean (b), ADCmin (c) and SUVmax (d). Bland–Altman plots of relative difference values (in %) of measurements (y-axis) against relative mean values (in %) of measurements (x-axis). The mean absolute difference (bias) and 95 % CI of the mean difference (1.96 SD) are equally indicated

Inter-observer reproducibility measurements in tumours of ADCmean (a), SUVmean (b), ADCmin (c) and SUVmax (d). Bland–Altman plots of relative difference values (in %) of measurements (y-axis) against relative mean values (in %) of measurements (x-axis). The mean absolute difference (bias) and 95 % CI of the mean difference (1.96 SD) are equally indicated

Correlation of ADC and SUV values

There was no correlation between ADC values (ADCmean, ADCmin, ADCmax) and SUV values (SUVmax, SUVmean or SUVmin) (r −0.103, −0.051; p 0.552, 0.777) (Fig. 5).

Scatter plots represent results of linear regression between ADCmean and SUVmean (a), ADCmean and SUVmax (b), ADCmin and SUVmean (c) and ADCmin and SUVmax (d). ADCs are expressed in 10−3 mm2/s. For each scatter plot, the best-fit line is shown. No statistically significant correlation was found between ADC and SUV values

ADC and SUV in relationship to the histologic grade

Table 5 summarizes the results of ADCmean and SUVmean of well, moderately and poorly differentiated HNSCC. No significant correlation was seen between the ADCmean and histologic grade (p = 0.216) or between SUVmean and histologic grade (p = 0.425). There was, however, a tendency of SUV to increase with dedifferentiation and a tendency of ADC to decrease with dedifferentiation (Table 5).

Discussion

Most DWI sequences routinely used in head and neck oncology are echo planar imaging (EPI)-based sequences [8, 13, 17, 22, 23]. Although the quality of EPI DWI images may be impaired by susceptibility artefacts, breathing or swallowing, we were able to correctly localize the tumours and to precisely position ROIs by fusing the b1000 and T2-weighted sequences (Figs. 1 and 2). As recently shown, the use of newer improved EPI technology, dedicated surface coils and optimized sequences enables a maximal reduction of EPI-related artefacts at a relatively high spatial resolution [8, 23–27]. In addition, by carefully instructing the patient not to move or swallow during image acquisition, good quality DWI images may be obtained in the vast majority of patients. In the current series, DWI images were of poor quality only in 1 of 34 patients (3 % non-diagnostic DWI).

As pointed out recently, in order to eliminate the effect of possible distortion due to susceptibility artefacts, ADC measurements should not be performed on ADC maps alone but the anatomic information from T1- or T2-weighted sequences should be taken into consideration when performing these measurements [8, 27, 28]. In the current study ADC measurements were performed using predefined ROIs saved in DICOM format and fusing the b1000 and T2-weighted images, thereby allowing optimal anatomic matching.

In our study we calculated the ADC of tumours from b values of 0 and 1,000 s/mm2. Such high b values eliminate the perfusion effect and have been used by most investigators for the evaluation of HNSCC [8, 17, 23, 24, 27–31].

The ADC values in the current series were obtained at 1.5 and 3 T. In theory, ADC values are independent of the magnetic field strength [32]. Having measured at least two different b values (such as b = 0 and b = 1,000 s/mm2), the logarithm of the relative signal intensity of a tissue is plotted on the y-axis against the b values on the x-axis. The slope of the line fitted through the plots describes the ADC [32]. This mono-exponential fitting is most often used in the literature [8, 17, 23, 27, 32]. Several investigators have compared ADC values of different tissues at different field strengths. With one exception [33], the vast majority of studies evaluating the influence of the magnetic field strength on ADC measurements at 1.5, 3 and 7 T found no statistically significant difference for ADC values either in the abdomen [34, 35], or in the head and neck [36, 37], brain [25, 38] or breast [38] provided that the parameters of the DWI sequence used were identical. Data of the current series showing no statistically significant difference between ADC values of HNSCC at 1.5 and 3 T are in coherence with the literature; in this retrospective series identical b values and parameters were used so that any possible variation is negligible at most.

Although ADC measurements are increasingly used in head and neck oncology, data regarding measurement reproducibility are very scarce both for HNSCC [17] and for nodal metastases from HNSCC [17, 22]. Our current data suggest that intra- and inter-observer agreement for ADC measurements are excellent (Figs. 3 and 4). Compared to the only series to date evaluating observer variability in HNSCC [17], we found a slightly superior inter-observer agreement (ICC = 0.95–0.96 versus reported 0.79) and a higher intra-observer agreement for ADC values (ICC = 0.98 versus reported 0.33) [17]. These results may be explained by the use of predefined ROIs matched for size and anatomic levels resulting in minimal inter- and intra-observer variability.

Currently, PET/CT is widely used for the pre-therapeutic evaluation of HNSCC and for the assessment of treatment response. In most studies, the most common quantitative approach used is to measure SUVmax because this value is not dependent on the size of the ROI used [13, 14, 39]. In addition, in routine clinical practice, SUVmean is often equally reported. While SUVmax does not depend on the observer, SUVmean may theoretically vary with the person who draws the ROI [39]. Several investigators have shown an excellent inter-observer reproducibility for SUVmax values for lung cancer [40], sarcomas [41], breast cancer and, more recently, for HNSCC [16]. In the current series, we found almost perfect SUVmean and SUVmax reproducibility with ICC values ranging from 0.97 to 0.99.

Both the ADC values and the SUV values of HNSCC in the current study are similar to those reported by previous investigators [13–15, 24, 29, 30, 42–46]. In our study, there was no statistically significant association between the histologic tumour grade and SUV or ADC values (Table 5), although we observed a trend towards higher SUV and lower ADC values in poorly differentiated as compared to well differentiated HNSCC (Table 5). A similar trend has been recently reported by another group [43].

Although SUV values mainly reflect cell proliferation, whereas ADC values mainly reflect tissue cellularity, it is still unclear whether both parameters may provide similar information with respect to viable tumour cells or degree of dedifferentiation. The question of whether these parameters are statistically correlated or independent is gaining increasing attention, as recent data suggest that both ADC and SUV values may be correlated with cell proliferation and tumour necrosis [1–4]. Our current study did not show a correlation between SUV and ADC(1000) values in HNSCC, indicating that these two biomarkers are independent biomarkers in HNSCC. Similar observations were made in a previous study [13, 14]; however, they were contradicted by another group who found a significant negative correlation between SUVmax and ADC(800) in 26 patients [15]. Correlating SUV and ADC values of tumours requires performing measurements on different imaging modalities at the same location within the tumour. Ideally, this should be performed by fusing MRI and PET/CT data sets. Although fusion of MRI and PET/CT data sets may be feasible using currently available anatomy-based fusion software, the quality of such multimodality fusion in the head and neck strongly depends on the anatomic tumour location. As recently suggested, the quality of data fusion above the hyoid bone may be good, whereas fusion quality below the hyoid bone may be fair to poor [47]. Until newly developed elastic fusion software may become more widely available, visual correlation using anatomic landmarks remains the most reliable way to precisely compare tumour levels on different imaging modalities. Although the possible correlation between SUV and ADC values is still a controversial issue, both parameters may accurately predict response to chemotherapy [15, 48]. Additional work thus appears necessary in order to determine how to interpret these biomarkers in a complementary fashion.

In conclusion, our study indicates that SUV and ADC values are independent parameters in HNSCC. Measurements of these two biomarkers were reproducible with almost perfect inter-observer and intra-observer agreements for both methods. Neither SUV nor ADC values were able to predict the histologic grade, although a trend towards higher SUV and lower ADC values was observed in poorly differentiated tumours. Further studies in larger patient populations may address the question of whether the complementary use of SUV and ADC values could be useful in the diagnosis of primary and recurrent HNSCC.

References

Argiris A, Karamouzis MV, Raben D, Ferris RL. Head and neck cancer. Lancet 2008;371:1695–709.

Al-Ibraheem A, Buck A, Krause BJ, Scheidhauer K, Schwaiger M. Clinical applications of FDG PET and PET/CT in head and neck cancer. J Oncol 2009;2009:208725.

Seitz O, Chambron-Pinho N, Middendorp M, Sader R, Mack M, Vogl TJ, et al. 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose-PET/CT to evaluate tumor, nodal disease, and gross tumor volume of oropharyngeal and oral cavity cancer: comparison with MR imaging and validation with surgical specimen. Neuroradiology 2009;51:677–86.

Jacob R, Welkoborsky HJ, Mann WJ, Jauch M, Amedee R. [Fluorine-18]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography, DNA ploidy and growth fraction in squamous-cell carcinomas of the head and neck. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec 2001;63:307–13.

Keen H, Pichler B, Kukuk D, Duchamp O, Raguin O, Shannon A, et al. An evaluation of 2-deoxy-2-[18F]fluoro-D-glucose and 3′-deoxy-3′-[18F]-fluorothymidine uptake in human tumor xenograft models. Mol Imaging Biol 2012;14:355–65.

Chen Z, Ma L, Lou X, Zhou Z. Diagnostic value of minimum apparent diffusion coefficient values in prediction of neuroepithelial tumor grading. J Magn Reson Imaging 2010;31:1331–8.

Zhang X-Y, Sun Y-S, Tang L, Xue W-C, Zhang X-P. Correlation of diffusion-weighted imaging data with apoptotic and proliferation indexes in CT26 colorectal tumor homografts in balb/c mouse. J Magn Reson Imaging 2011;33:1171–6.

Thoeny HC, De Keyzer F, King AD. Diffusion-weighted MR imaging in the head and neck. Radiology 2012;263:19–32.

Wong CS, Gong N, Chu Y-C, Anthony M-P, Chan Q, Lee HF, et al. Correlation of measurements from diffusion weighted MR imaging and FDG PET/CT in GIST patients: ADC versus SUV. Eur J Radiol 2011;81:2122–6.

Regier M, Derlin T, Schwarz D, Laqmani A, Henes FO, Groth M, et al. Diffusion weighted MRI and 18F-FDG PET/CT in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): does the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) correlate with tracer uptake (SUV)? Eur J Radiol 2012;81:2913–8.

Ho K-C, Lin G, Wang J-J, Lai C-H, Chang C-J, Yen T-C. Correlation of apparent diffusion coefficients measured by 3T diffusion-weighted MRI and SUV from FDG PET/CT in primary cervical cancer. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2009;36:200–8.

Wu X, Korkola P, Pertovaara H, Eskola H, Järvenpää R, Kellokumpu-Lehtinen P-L. No correlation between glucose metabolism and apparent diffusion coefficient in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a PET/CT and DW-MRI study. Eur J Radiol 2011;79:e117–21.

Fruehwald-Pallamar J, Czerny C, Mayerhoefer ME, Halpern BS, Eder-Czembirek C, Brunner M, et al. Functional imaging in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: correlation of PET/CT and diffusion-weighted imaging at 3 Tesla. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2011;38:1009–19.

Choi SH, Paeng JC, Sohn C-H, Pagsisihan JR, Kim Y-J, Kim KG, et al. Correlation of 18F-FDG uptake with apparent diffusion coefficient ratio measured on standard and high b value diffusion MRI in head and neck cancer. J Nucl Med 2011;52:1056–62.

Nakajo M, Nakajo M, Kajiya Y, Tani A, Kamiyama T, Yonekura R, et al. FDG PET/CT and diffusion-weighted imaging of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: comparison of prognostic significance between primary tumor standardized uptake value and apparent diffusion coefficient. Clin Nucl Med 2012;37:475–80.

Jackson T, Chung MK, Mercier G, Ozonoff A, Subramaniam RM. FDG PET/CT interobserver agreement in head and neck cancer: FDG and CT measurements of the primary tumor site. Nucl Med Commun 2012;33:305–12.

Verhappen MH, Pouwels PJW, Ljumanovic R, van der Putten L, Knol DL, De Bree R, et al. Diffusion-weighted MR imaging in head and neck cancer: comparison between half-Fourier acquired single-shot turbo spin-echo and EPI techniques. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2012;33:1239–46.

Huang SC. Anatomy of SUV. Standardized uptake value. Nucl Med Biol 2000;27:643–6.

Donner A, Koval JJ. The estimation of intraclass correlation in the analysis of family data. Biometrics 1980;36:19–25.

Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977;33:159–74.

Kruskal W, Wallis A. Use of ranks in one-criterion variance Analysis. J Am Stat Assoc 1952;47:583.

Kwee TC, Takahara T, Luijten PR, Nievelstein RAJ. ADC measurements of lymph nodes: inter- and intra-observer reproducibility study and an overview of the literature. Eur J Radiol 2010;75:215–20.

Vandecaveye V, De Keyzer F, Vander Poorten V, Dirix P, Verbeken E, Nuyts S, et al. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: value of diffusion-weighted MR imaging for nodal staging. Radiology 2009;251:134–46.

Vandecaveye V, Dirix P, De Keyzer F, de Beeck KO, Vander Poorten V, Roebben I, et al. Predictive value of diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging during chemoradiotherapy for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Eur Radiol 2010;20:1703–14.

Choi S, Cunningham DT, Aguila F, Corrigan JD, Bogner J, Mysiw WJ, et al. DTI at 7 and 3 T: systematic comparison of SNR and its influence on quantitative metrics. Magn Reson Imaging 2011;29:739–51.

Vandecaveye V, De Keyzer F, Nuyts S, Deraedt K, Dirix P, Hamaekers P, et al. Detection of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma with diffusion weighted MRI after (chemo)radiotherapy: correlation between radiologic and histopathologic findings. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2007;67:960–71.

Tshering Vogel DW, Zbaeren P, Geretschlaeger A, Vermathen P, De Keyzer F, Thoeny HC. Diffusion-weighted MR imaging including bi-exponential fitting for the detection of recurrent or residual tumour after (chemo)radiotherapy for laryngeal and hypopharyngeal cancers. Eur Radiol 2013;23:562–9.

Wang J, Takashima S, Takayama F, Kawakami S, Saito A, Matsushita T, et al. Head and neck lesions: characterization with diffusion-weighted echo-planar MR imaging. Radiology 2001;220:621–30.

Haerle SK, Huber GF, Hany TF, Ahmad N, Schmid DT. Is there a correlation between 18F-FDG-PET standardized uptake value, T-classification, histological grading and the anatomic subsites in newly diagnosed squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck? Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 2010;267:1635–40.

Imsande HM, Davison JM, Truong MT, Devaiah AK, Mercier GA, Ozonoff AJ, et al. Use of 18F-FDG PET/CT as a predictive biomarker of outcome in patients with head-and-neck non-squamous cell carcinoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2011;197:976–80.

Chawla S, Kim S, Wang S, Poptani H. Diffusion-weighted imaging in head and neck cancers. Future Oncol 2009;5:959–75.

Koh D-M, Collins DJ. Diffusion-weighted MRI in the body: applications and challenges in oncology. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2007;188:1622–35.

Huisman TAGM, Loenneker T, Barta G, Bellemann ME, Hennig J, Fischer JE, et al. Quantitative diffusion tensor MR imaging of the brain: field strength related variance of apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) and fractional anisotropy (FA) scalars. Eur Radiol 2006;16:1651–8.

Rosenkrantz AB, Oei M, Babb JS, Niver BE, Taouli B. Diffusion-weighted imaging of the abdomen at 3.0 Tesla: image quality and apparent diffusion coefficient reproducibility compared with 1.5 Tesla. J Magn Reson Imaging 2011;33:128–35.

Notohamiprodjo M, Dietrich O, Horger W, Horng A, Helck AD, Herrmann KA, et al. Diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) of the kidney at 3 tesla-feasibility, protocol evaluation and comparison to 1.5 Tesla. Invest Radiol 2010;45:245–54.

Kim S, Loevner L, Quon H, Sherman E, Weinstein G, Kilger A, et al. Diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance imaging for predicting and detecting early response to chemoradiation therapy of squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck. Clin Cancer Res 2009;15:986–94.

Fushimi Y, Miki Y, Okada T, Yamamoto A, Mori N, Hanakawa T, et al. Fractional anisotropy and mean diffusivity: comparison between 3.0-T and 1.5-T diffusion tensor imaging with parallel imaging using histogram and region of interest analysis. NMR Biomed 2007;20:743–8.

Matsuoka A, Minato M, Harada M, Kubo H, Bandou Y, Tangoku A, et al. Comparison of 3.0- and 1.5-tesla diffusion-weighted imaging in the visibility of breast cancer. Radiat Med 2008;26:15–20.

Burger IA, Huser DM, Burger C, Von Schulthess GK, Buck A. Repeatability of FDG quantification in tumor imaging: averaged SUVs are superior to SUV(max). Nucl Med Biol 2012;39:666–70.

Jacene HA, Leboulleux S, Baba S, Chatzifotiadis D, Goudarzi B, Teytelbaum O, et al. Assessment of interobserver reproducibility in quantitative 18F-FDG PET and CT measurements of tumor response to therapy. J Nucl Med 2009;50:1760–9.

Benz MR, Evilevitch V, Allen-Auerbach MS, Eilber FC, Phelps ME, Czernin J, et al. Treatment monitoring by 18F-FDG PET/CT in patients with sarcomas: interobserver variability of quantitative parameters in treatment-induced changes in histopathologically responding and nonresponding tumors. J Nucl Med 2008;49:1038–46.

Srinivasan A, Dvorak R, Rohrer S, Mukherji SK. Initial experience of 3-tesla apparent diffusion coefficient values in characterizing squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck. Acta Radiol 2008;49:1079–84.

Ichikawa Y, Sumi M, Sasaki M, Sumi T, Nakamura T. Efficacy of diffusion-weighted imaging for the differentiation between lymphomas and carcinomas of the nasopharynx and oropharynx: correlations of apparent diffusion coefficients and histologic features. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 2012;33:761–6.

Machtay M, Natwa M, Andrel J, Hyslop T, Anne PR, Lavarino J, et al. Pretreatment FDG-PET standardized uptake value as a prognostic factor for outcome in head and neck cancer. Head Neck 2009;31:195–201.

Higgins KA, Hoang JK, Roach MC, Chino J, Yoo DS, Turkington TG, et al. Analysis of pretreatment FDG-PET SUV parameters in head-and-neck cancer: tumor SUVmean has superior prognostic value. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2012;82:548–53.

Wong RJ, Lin DT, Schöder H, Patel SG, Gonen M, Wolden S, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic value of [(18)F]fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography for recurrent head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:4199–208.

Masterson K, Rager O, Kohler R, Wissmeyer M, Ratib O, Becker M. MR/PET image fusion: feasibility and utility in the loco-regional assessment of head and neck cancer. SS415, Proceedings of the 11th Annual Congress Swiss Society of Nuclear Medicine, 3–5 June 2010, Lugano. Nuklearmed-Nucl Med 2010;49(3):A127.

Park SH, Moon WK, Cho N, Chang JM, Im S-A, Park IA, et al. Comparison of diffusion-weighted MR imaging and FDG PET/CT to predict pathological complete response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with breast cancer. Eur Radiol 2012;22:18–25.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Benedicte Delattre, Ph.D. for statistical advice.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Varoquaux, A., Rager, O., Lovblad, KO. et al. Functional imaging of head and neck squamous cell carcinoma with diffusion-weighted MRI and FDG PET/CT: quantitative analysis of ADC and SUV. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 40, 842–852 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-013-2351-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-013-2351-9