Abstract

Purpose

In peptide-receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT), the maximum activity dose that can safely be administered is limited by high renal uptake and retention of radiolabelled peptides. The kidney radiation dose can be reduced by coinfusion of agents that competitively inhibit the reabsorption of radiolabelled peptides, such as positively charged amino acids, Gelofusine, or trypsinised albumin. The aim of this study was to identify more specific and potent inhibitors of the kidney reabsorption of radiolabelled peptides, based on albumin.

Methods

Albumin was fragmented using cyanogen bromide and six albumin-derived peptides with different numbers of electric charges were selected and synthesised. The effect of albumin fragments (FRALB-C) and selected albumin-derived peptides on the internalisation of 111In-albumin, 111In-minigastrin, 111In-exendin and 111In-octreotide by megalin-expressing cells was assessed. In rats, the effect of Gelofusine and albumin-derived peptides on the renal uptake and biodistribution of 111In-minigastrin, 111In-exendin and 111In-octreotide was determined.

Results

FRALB-C significantly reduced the uptake of all radiolabelled peptides in vitro. The albumin-derived peptides showed different potencies in reducing the uptake of 111In-albumin, 111In-exendin and 111In-minigastrin in vitro. The most efficient albumin-derived peptide (peptide #6), was selected for in vivo testing. In rats, 5 mg of peptide #6 very efficiently inhibited the renal uptake of 111In-minigastrin, by 88%. Uptake of 111In-exendin and 111In-octreotide was reduced by 26 and 33%, respectively.

Conclusions

The albumin-derived peptide #6 efficiently inhibited the renal reabsorption of 111In-minigastrin, 111In-exendin and 111In-octreotide and is a promising candidate for kidney protection in PRRT.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Excretion of radiolabelled hydrophilic peptides and small proteins occurs largely via the kidneys. In peptide-receptor radionuclide therapy (PRRT), rapid clearance of the radiolabelled peptides from the blood and low retention in the kidneys are important to minimise the radiation dose to normal tissues. However, as outlined in more detail previously [1], a part of the filtered load of these small proteins and peptides is reabsorbed from the ultrafiltrate in the proximal tubules and retained there, exposing the kidneys to a relatively high radiation dose. Indeed, acute and chronic kidney damage have been described in patients receiving PRRT and in animal models [2–5] and kidney toxicity is currently dose-limiting in PRRT [3, 4, 6]. Reduction of the renal radiation dose by reducing the renal retention of radiolabelled peptides facilitates the administration of higher activity doses in PRRT, which is expected to increase its therapeutic effect.

A possible approach to reducing the renal reabsorption of radiolabelled peptides is to interfere with endocytic receptors on the proximal tubular cells. The receptors involved in the tubular reabsorption of peptides have not yet been characterised completely, but for various peptides, involvement of megalin and cubilin has been shown [7–10]. Cubilin is a large extracellular receptor that depends on other receptors such as megalin for its internalisation. Megalin is a multiligand receptor belonging to the LDL receptor family. The receptor contains four large cysteine-rich ligand binding domains and is a high-capacity transport system with varying affinity for the reabsorption of a large series of structurally non-related compounds, such as albumin, vitamin D binding protein, β2-microglobulin, aprotinin, Ca2+, etc. [7, 11, 12]. Charges may play an important role in the binding of ligands to megalin [12, 13] or to other renal receptors. Gotthardt et al. found a positive correlation between the renal retention and the total number of charged amino acid residues of radiolabelled peptides, and suggested a causal relationship [14]. It has been shown that some ligands bind to megalin via their cationic sites and that co-administration of cationic compounds can inhibit the renal reabsorption of these ligands [8, 15]. Indeed, in patients undergoing PRRT with radiolabelled somatostatin analogues as well as in various animal models, the renal uptake of different radiolabelled peptides and antibody fragments can effectively be reduced by co-administration of basic amino acids [16–19]. However, these compounds can cause side-effects at high doses, such as nausea, hyperkalemia, arrhythmias and even nephrotoxicity [15, 18, 20]. Succinylated gelatin (Gelofusine, Gelo), a plasma expander that consists of a mixture of collagen-derived peptides, has also been shown to efficiently reduce the renal reabsorption of various radiolabelled peptides in animals, and of 111In-octreotide in humans [1, 21–23]. Nevertheless, more efficient inhibitors are needed since none of these substances completely inhibits the reabsorption of radiolabelled peptides.

Albumin, the most abundant plasma protein, is a natural ligand of megalin and cubilin. Due to albumin’s size and charge (67 kDa, predominantly anionic at physiological pH), only a small fraction of circulating albumin is filtered in the glomeruli [13, 24, 25]. This small fraction is subsequently reabsorbed by megalin/cubilin-mediated endocytosis. Previously, we showed that peptide fragments obtained by trypsinisation of bovine serum albumin (BSA) reach higher concentrations in the proximal tubules than intact albumin and are efficient inhibitors of the renal reabsorption of 111In-octreotide, 111In-exendin and 111In-minigastrin in rats [1]. However, trypsin cleaves peptides at the carboxyl terminus of arginine and lysine residues [26]. Since BSA contains 78 arginine and lysine residues, its trypsinisation yields a complex mixture of many different albumin fragments. We hypothesised that some of these may not actually contribute to the blocking of the renal reuptake of radiolabelled peptides, but might cause side effects. Better defined albumin fragments may be obtained by digestion of albumin by cyanogen bromide (CNBr) in formic acid. CNBr cleaves peptides at the carboxyl terminus of methionine residues and formic acid cleaves peptides at aspartic acid–proline bonds [27]. BSA has four methionine residues and two aspartic acid–proline bonds. Thus, digestion of BSA by CNBr in formic acid yields a maximum of 28 possible fragments.

Since megalin binds various structurally different peptides and proteins, we hypothesised that different fragments of albumin may bind to megalin and be potential candidates for inhibiting the renal reuptake of radiolabelled peptides. In addition to the mixture of CNBr-digested albumin fragments (FRALB-C), a set of albumin-derived peptides was selected. The selection of these peptides was based on the distribution of charged amino acid residues in BSA. We aimed to identify albumin fragments that potently inhibit the renal reabsorption of radiolabelled peptides, in order to maximise the inhibitory effect and to minimise potential side effects.

In this study, the effect of FRALB-C and a series of synthesised albumin-derived peptides on the renal uptake of [111In-DTPA-d-Phe1]-octreotide (111In-octreotide), [Lys40(aminohexanoic acid-DTPA-111In)NH2]-exendin-3 (111In-exendin) and [111In-DOTA-Glu1]-minigastrin (111In-minigastrin) was analyzed, both in vitro and in rats.

Materials and methods

Fragmentation of albumin

Intact BSA (2.26 µmol (150 mg), Sigma) was added to 4.5 ml of 70% v/v formic acid with dithiothreitol (6.7 mM) and heated for 2 min at 100°C. Subsequently, 1.13 mmol of CNBr (Sigma) was added and the mixture was incubated for 24 h at room temperature in the dark, followed by 5 min of incubation at 50°C. The acid was neutralised by adding 9 ml of 4-ethylmorpholine (Sigma), after which the mixture was dialyzed against phosphate buffered saline (PBS). The fragmented albumin was analyzed by fast protein liquid chromatography (FPLC) and sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). The protein concentration in the FRALB-C mixture was determined with the Bio-Rad Protein Assay using intact BSA as a reference.

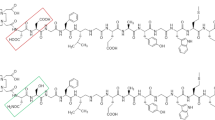

Selection and synthesis of albumin fragments

Six parts of the BSA amino acid sequence were selected for peptide synthesis. The selection was based on the distribution of charged amino acid residues in these sequences and their net charge at physiological pH. Five peptides containing different combinations of positive and negative charges were selected and synthesised, each composed of 16 amino acid residues. An uncharged peptide was synthesised as well, but this was not studied since it could not be dissolved in water. A sixth peptide was synthesised, which was the smallest possible fragment formed after CNBr digestion of BSA, consisting of the 36 C-terminal amino acid residues. The characteristics of the synthesised peptides are summarised in Table 1. Peptides were synthesised by standard solid-phase F-moc chemistry and purified by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) at Peptide Specialty Laboratories GmbH (Heidelberg, Germany) and at Peptide 2.0 (Chantilly, VA, USA).

Other compounds used to reduce renal reabsorption

Gelofusine (Gelo, Braun) is a solution of succinylated gelatin fragments (40 g/l). The molecular mass of these fragments in Gelo averages 30 kDa. Intact BSA was dissolved in PBS at a concentration of 100 g/l. Lysine solution was prepared as a 160 g/l solution in PBS.

Radiolabeling

[DTPA-d-Phe1]-octreotide (Octreoscan, Covidien) was labelled with 111In by adding 37 MBq of 111InCl3 (Covidien) to 1 µg of Octreoscan and incubating for 30 min at room temperature. [Lys40(Ahx-DTPA)NH2]-exendin-3 (exendin, Peptide Specialty Laboratories GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany) was synthesised using standard F-moc chemistry. The peptide was labelled with 111InCl3 in a 0.1 M 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid (MES) buffer, pH 5.5. A mixture of 19 MBq of 111In and 1 µg of exendin was incubated for 30 min at room temperature. [DOTA-Glu1]-minigastrin (minigastrin, Peptide Specialty Laboratories) was synthesised using standard F-moc chemistry. Minigastrin was labelled with 111InCl3 in a 0.25 M ammonium acetate buffer, pH 5.5. 111InCl3 (22.2 MBq) was added to 1 µg of minigastrin and the mixture was incubated at 95°C for 25 min.

BSA was conjugated with DTPA as described by Hnatowich et al. [28] and labelled with 111In by adding 11 MBq of 111InCl3 to 1 µg of DTPA-BSA in a 0.25 M ammonium acetate buffer, pH 5.5 (100 µl) and incubating for 20 min at room temperature. Radiochemical purity and labeling efficiency of the labelled peptides and proteins were determined by silica gel instant thin layer chromatography and reverse phase HPLC.

In vitro studies

Rat yolk sac epithelial (BN16) cells, expressing megalin and cubilin [29, 30] were kindly provided by Prof. P.J. Verroust. Cells were cultured at 37°C in BN16 medium, consisting of Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium plus 4.5 g/l glucose (Invitrogen) with 10% fetal calf serum, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (Invitrogen).

The potency of FRALB-C to inhibit the interaction of the radiolabelled peptides with BN16 cells was determined in vitro in triplicate. The cells were seeded into 6-well plates at 3 × 105 cells/well and cultured until confluent. The cells were washed with PBS and incubated for 1 h with serum-free BN16 medium. The cells were washed again with PBS, and 2 ml of Ringer’s solution (Braun) with 10 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) buffer, pH 7.4 was added. Subsequently, 100 µl of the inhibitor was added: either PBS, Gelo or 100 µg of FRALB-C. Directly after addition of the inhibitor, 80 kBq (50 µl) of 111In-albumin, 111In-octreotide, 111In-exendin or 111In-minigastrin was added. After 1 h of incubation at 37°C, cells were rinsed with Ringer’s solution and harvested using cotton swabs. Radioactivity was measured in a shielded well-type gamma counter (Wizard, Wallac). To study the inhibitory potency of the albumin-derived peptides, the same procedure was used. Increasing doses of the six peptides (10, 30 and 100 µg per incubation) were compared with the potency of intact albumin (10 mg) and Gelo (5 mg) to reduce the binding of 111In-albumin, 111In-exendin and 111In-minigastrin. Internalisation of these radiolabelled compounds by BN16 cells was studied using essentially the same assay. Cells were incubated with 111In-albumin, 111In-exendin or 111In-minigastrin for 1 h at 37°C or 0°C. Internalised activity and cell-surface bound activity was determined by incubating the cells for 10 min in 1 ml 0.1 M acetic acid, 154 mM NaCl, pH 2.8 at 0°C. The activity in the supernatant (cell-surface bound) and the activity in the cells (internalised) was determined.

Animal studies

Groups of five male Wistar rats (200–220 g) were used in all experiments. The potency of FRALB-C to inhibit the renal reabsorption of 111In-octreotide was compared with the reference agents PBS, lysine and Gelo. The animals were injected i.v. with 0.5 ml of the inhibitor (either PBS, lysine (80 mg), Gelo (20 mg) or FRALB-C (1 mg, 5 mg or 20 mg)) via the tail vein. One minute later, 111In-octreotide was injected i.v. (2 MBq/rat).

The animals were killed 20 h after injection and a blood sample was drawn and organs were dissected. The kidneys, adrenals, spleen and stomach, as well as samples of muscle, lung, pancreas, liver and duodenum were harvested. The tissues were weighed and counted in a shielded well-type gamma counter together with the injection standards. Radioactivity concentration was expressed as percentage of the injected dose per gram tissue (% ID/g).

The albumin-derived peptide which most potently reduced the binding of 111In-minigastrin and 111In-exendin in the cell binding assay, peptide #6, was studied in rats according to the same procedure. The effect of peptide #6 (0.2 mg, 1 mg or 5 mg per rat) on the uptake of 111In-minigastrin, 111In-exendin and 111In-octreotide was studied and compared to PBS and Gelo (20 mg per rat) as negative and positive control, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean % reduction ± standard deviation. The analysis of differences in cell binding and kidney uptake was performed using Student’s t-test. Biodistribution data in other organs were analyzed by one-way ANOVA. The significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

Radiolabelling

Radiochemical purity and labelling efficiency of all compounds were higher than 95%.

In vitro studies

The internalisation assay showed that at 37°C, >90% of cell-associated 111In-albumin and 111In-minigastrin and >75% of 111In-exendin was internalised (data not shown). This indicates that these radiolabelled compounds were rapidly internalised by the BN16 cells.

As summarised in Fig. 1, FRALB-C significantly reduced the uptake of all radiolabelled peptides in BN16 cells. A dose of 100 µg of FRALB-C per incubation reduced the uptake of 111In-albumin by 75% ± 5.7% (p < 0.001, Fig. 1a). The uptake of 111In-minigastrin, -exendin and -octreotide was reduced by 95% ± 6.3% (p < 0.001), 67% ± 6.9% (p < 0.001) and 39% ± 7.4% (p < 0.01), respectively (Fig. 1b–d). The lower doses of 30 µg and 10 µg FRALB-C were less effective (data not shown). Gelofusine (4 mg) significantly reduced the uptake of all radiolabelled peptides as well.

The effects of 100 µg of the six albumin-derived peptides on the uptake of 111In-albumin, -minigastrin and -exendin in BN16 cells are summarised in Fig. 2. The uptake of 111In-albumin (Fig. 2a) was inhibited significantly (all p < 0.003) by peptide #1 (54% ± 9.3%), peptide #3 (50% ± 9.1%), peptide #5 (37% ± 11%) and most potently by peptide #6 (75% ± 9.1%), as well as by intact albumin (91% ± 9.1%) and Gelo (65% ± 9.0%).

As depicted in Fig. 2b, the uptake of 111In-minigastrin was reduced significantly by peptide #3 (60% ± 6.0%, p = 0.002), peptide #4 (76% ± 4.5%, p = 0.0002), peptide #5 (37% ± 5.7%, p = 0.005) and peptide #6 (96% ± 4.3%, p < 0.0001). Albumin and Gelo also significantly reduced the uptake, by 90% ± 4.5% and by 98% ± 4.3% respectively (both p < 0.0002).

The uptake of 111In-exendin by BN16 cells (Fig. 2c) was reduced significantly by peptide #3 (42% ± 6.2%, p = 0.001), peptide #5 (18% ± 6.4%, p = 0.03) and most potently by peptide #6 (94% ± 6.1%, p < 0.0001), as well as by albumin and Gelo (94% ± 6.2% and 91% ± 6.1% respectively, both p < 0.0001).

The lower doses of 30 µg and 10 µg of the albumin-derived peptides were less effective in inhibiting the uptake of these 111In-labelled peptides (data not shown).

Animal studies

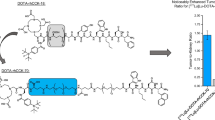

The effect of FRALB-C on the renal retention of 111In-octreotide in rats is summarised in Fig. 3. FRALB-C (1 mg) reduced the renal uptake of 111In-octreotide by 24% ± 12% (p = 0.02). Higher doses of FRALB-C (up to 20 mg) did not increase this effect. Lysine (80 mg) and Gelo (20 mg) reduced the uptake by 36% ± 11% and 27% ± 9.7%, respectively (both p < 0.003). FRALB-C had no significant effect on the uptake of 111In-octreotide in the pancreas, adrenals or other organs.

Kidney activity concentrations 20 h after i.v. injection of 111In-octreotide in rats. One to three minutes prior to the injection of 111In-octreotide, groups of five rats received 0.5 ml of either PBS, lysine (80 mg), Gelo (20 mg) or FRALB-C (1 mg). Results are presented as mean %ID/g, error bars indicate SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.005

Figure 4 summarises the effect of peptide #6 on the renal retention of 111In-minigastrin, 111In-exendin and 111In-octreotide in rats. Peptide #6 had a pronounced effect on the renal uptake of 111In-minigastrin: 5 mg of peptide #6 reduced the uptake by 88% ± 9.0% (p < 0.0001). Gelo reduced the uptake by 77% ± 8.9% (p < 0.0001). The renal uptake of 111In-exendin was reduced by 26% ± 3.4% by peptide #6, whereas Gelo reduced the uptake by 16% ± 3.1% (both p < 0.0001). The highest dose of peptide #6 reduced the uptake of 111In-octreotide by 33% ± 13% (p = 0.004), comparable to the effect of 20 mg of Gelo (28% ± 9.9%, p = 0.002). The lower doses of 1 mg and 0.2 mg of peptide #6 were less effective in inhibiting the renal uptake of the 111In-labelled peptides.

Kidney activity concentrations 20 h after i.v. injection of 111In-minigastrin (a), 111In-exendin (b) or 111In-octreotide (c) in rats. One to three minutes prior to the injection of the 111In-labelled peptide, groups of five rats received 0.5 ml of either PBS, Gelo (20 mg) or albumin-derived peptide #6. Results are presented as mean %ID/g, error bars indicate SEM. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.005

Peptide #6 significantly reduced the uptake of 111In-octreotide in the adrenals, by 42% ± 13% (p = 0.0008), whereas the uptake in the pancreas and other organs was unaffected (Fig. 5). The uptake of 111In-minigastrin and 111In-exendin in organs other than the kidneys was not affected by peptide #6 and no adverse effects of its injection were noted.

Discussion

Radiation-induced chronic renal damage due to proximal tubular reabsorption and retention of radiolabelled peptides limits the activity dose that can safely be administered in PRRT, thereby limiting the efficacy of this anti-tumour therapy. The renal reabsorption of 111In-octreotide is, at least in part, mediated by megalin [9]. Megalin is a multiligand scavenger receptor that is involved in the renal reuptake of various peptides and proteins, among which albumin [12, 13]. We previously reported that both the protein-based plasma expander Gelo and trypsinised albumin are effective inhibitors of the renal reabsorption of various radiolabelled peptides [1, 21, 22]. In the current study, we aimed to identify albumin-derived peptides that are effective inhibitors of the renal uptake of 111In-labelled minigastrin, exendin and octreotide.

FRALB-C, bovine serum albumin fragmented by cyanogen bromide, proved to be an effective inhibitor of the uptake of 111In-labelled albumin, minigastrin, exendin and octreotide in megalin-expressing cells. In rats, FRALB-C inhibited the renal reabsorption of 111In-octreotide as efficiently as Gelo. The inhibitory effect of FRALB-C was comparable to the effects we previously obtained with trypsinised albumin [1].

FRALB-C is a mixture of at most 28 different albumin fragments. We expected these different fragments to have different affinities for megalin. Therefore, we aimed to further identify specific albumin fragments that inhibited the renal reuptake of radiolabelled peptides efficiently. However, attempts to further purify the FRALB-C mixture by filtration, dialysis and HPLC did not yield sufficiently purified peptides.

Six albumin-derived peptides were screened for their ability to reduce the uptake of 111In-albumin, 111In-exendin and 111In-minigastrin in cells expressing megalin and cubilin. The uptake of 111In-albumin was inhibited by peptides #1, #3, #5 and most potently by #6, whereas peptides # 2 and #4 did not have a significant effect. This suggests that the amino acid sequences of peptides #1, #3, #5 and #6 may be involved in the physiological binding of albumin to its renal receptors. However, since megalin’s binding domains facilitate the binding of various endogenous and exogenous peptides, it is also possible that some or all of these sequences are not actually involved in the binding of intact albumin to megalin; for example because they may not be exposed at the surface of the albumin molecule. Each of the peptides #1, #3, #5 and #6 contained both positively and negatively charged amino acid residues, whereas peptides #2 and #4 contained only positive or only negative charges, respectively. It was suggested previously that the distribution of charges rather than the overall charge may be important for ligand binding to megalin [13]. Our results suggest that both positive and negative charges might contribute to the binding of albumin to megalin and / or cubilin.

Exendin contains four positively charged and six negatively charged amino acid residues, minigastrin contains seven negatively charged amino acid residues and octreotide contains one positively charged amino acid residue. Similarly to 111In-albumin, the uptake of 111In-exendin by BN16 cells was reduced significantly by peptides #3, #5 and most potently by #6, suggesting that the binding mechanism of 111In-exendin might be similar to that of 111In-albumin. In addition to peptides #3, #5 and #6, peptide #4 significantly reduced the uptake of the exclusively negatively charged 111In-minigastrin as well. Each of the peptides #3–6 contained at least four negatively charged amino acid residues, whereas the peptides that did not reduce the binding of 111In-minigastrin contained three (peptide #1) and 0 (peptide #2) negative charges. This again suggests involvement of minigastrin’s multiple negative charges in its renal reuptake. It has been shown previously that the effect of polyglutamic acid chains on the renal reuptake of minigastrin depends on the number of negatively charged residues in these chains [31].

Peptide #6, the larger peptide, inhibited the uptake of 111In-albumin, 111In-exendin and 111In-minigastrin most effectively in vitro, although it was tested at a lower molar concentration than the other peptides. Whether its size, its charge distribution or other properties determine its effectiveness remains to be investigated. This peptide was subsequently studied in vivo.

In rats, peptide #6 reduced the renal uptake of 111In-minigastrin very effectively. The effect of 5 mg of peptide #6 was larger than the effect of 20 mg Gelo. The inhibition of the renal uptake of 111In-exendin by peptide #6 was less pronounced, although its effects on the cell binding of 111In-minigastrin and 111In-exendin were comparable in vitro. A possible explanation for the observed difference is a relatively short plasma half life of peptide #6. Literature suggests longer plasma half lives for exendin than for minigastrin [23, 33]. Peptide #6 might be largely excreted, while exendin is still present in relatively high concentrations in the plasma and the ultrafiltrate. In our previous study [1], trypsinised albumin had more effect on the renal uptake of 111In-exendin than peptide #6 had in this study, which might be explained by a longer half life of this mixture of peptides. Alternative possible explanations for the observed differences between 111In-exendin and 111In-minigastrin in vitro and in vivo include different mechanisms of renal reabsorption (e.g. involvement of different transporters or receptors), a higher affinity of exendin for renal receptors, or general differences in transport mechanisms and kinetics between the kidneys in vivo and the in vitro model.

The inhibition of the renal reabsorption of 111In-exendin and 111In-octreotide by 5 mg of peptide #6 in rats was comparable to the effects of 20 mg Gelo. The effect of FRALB-C on the renal uptake of 111In-octreotide was in the same range. Most other studies using competitive blockers to reduce the renal retention of 111In-octreotide report maximum reductions of around 50% [1, 15, 20–22]. The residual uptake may indicate a contribution of other mechanisms of renal reuptake, such as fluid phase endocytosis [34].

Remarkably, peptide #6 significantly reduced the uptake of 111In-octreotide in the adrenals. Since rat adrenals predominantly express somatostatin receptor subtype 2 (sstr2) [35] and 111In-octreotide has the highest affinity for sstr2 and lower affinities for sstr3 and sstr5 [36], this possibly indicates interference of peptide #6 with the binding of octreotide to sstr2. However, uptake in other organs known to express relatively high levels of sstr2, such as the pancreas and the stomach [37–39], was unaffected. Other mechanisms for the reduced uptake of 111In-octreotide in the adrenals have to be considered and future experiments will have to investigate if specific tumour uptake is affected by peptide #6. Although the peptide is derived from albumin and we did not observe any side-effects in the animal experiments, it is a new substance which may cause toxicity at higher doses. Therefore, the dose of this peptide that can be administered safely has to be determined before clinical use becomes possible.

In summary, peptide #6 is a promising candidate for inhibition of the renal reabsorption of 111In-minigastrin and perhaps of 111In-exendin. To reduce the renal reabsorption of radiolabelled peptides more efficiently, a combination of two or more competitive inhibitors of endocytosis and other approaches may prove to be useful.

Conclusion

Albumin digested by CNBr (FRALB-C) efficiently reduced the uptake of 111In-labelled albumin, octreotide, minigastrin and exendin in megalin expressing cells, and reduced the renal retention of 111In-octreotide in rats. In vitro, the effect of albumin-derived peptide #6 on the uptake of 111In-exendin and 111In-minigastrin was comparable to the effect of FRALB-C and Gelofusine. In rats, peptide #6 efficiently reduced the renal retention of 111In-labelled octreotide, exendin and especially minigastrin, opening up new possibilities for the reduction of kidney damage in peptide receptor radionuclide therapy with less chance of side-effects.

References

Vegt E, van Eerd JE, Eek A, et al. Reducing renal uptake of radiolabeled peptides using albumin fragments. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:1506–11.

Rolleman EJ, Krenning EP, Bernard BF, et al. Long-term toxicity of [(177)Lu-DOTA (0), Tyr (3)]octreotate in rats. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2007;34:219–27.

Cybulla M, Weiner SM, Otte A. End-stage renal disease after treatment with 90Y-DOTATOC. Eur J Nucl Med. 2001;28:1552–4.

Bodei L, Cremonesi M, Ferrari M, et al. Long-term evaluation of renal toxicity after peptide receptor radionuclide therapy with 90Y-DOTATOC and 177Lu-DOTATATE: the role of associated risk factors. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2008;35:1847–56.

Otte A, Herrmann R, Heppeler A, et al. Yttrium-90 DOTATOC: first clinical results. Eur J Nucl Med. 1999;26:1439–47.

Wessels BW, Konijnenberg MW, Dale RG, et al. MIRD pamphlet No. 20: the effect of model assumptions on kidney dosimetry and response--implications for radionuclide therapy. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:1884–99.

Christensen EI, Birn H, Verroust P, Moestrup SK. Megalin-mediated endocytosis in renal proximal tubule. Ren Fail. 1998;20:191–9.

Mogensen CE, Solling. Studies on renal tubular protein reabsorption: partial and near complete inhibition by certain amino acids. Scand J Clin Lab Invest. 1977;37:477–86.

de Jong M, Barone R, Krenning E, et al. Megalin is essential for renal proximal tubule reabsorption of (111)In-DTPA-octreotide. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:1696–700.

Baines RJ, Brunskill NJ. The molecular interactions between filtered proteins and proximal tubular cells in proteinuria. Nephron Exp Nephrol. 2008;110:e67–71.

Christensen EI, Verroust PJ. Megalin and cubilin, role in proximal tubule function and during development. Pediatr Nephrol. 2002;17:993–9.

Orlando RA, Exner M, Czekay RP, et al. Identification of the second cluster of ligand-binding repeats in megalin as a site for receptor-ligand interactions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:2368–73.

Birn H, Christensen EI. Renal albumin absorption in physiology and pathology. Kidney Int. 2006;69:440–9.

Gotthardt M, van Eerd-Vismale J, Oyen WJ, et al. Indication for different mechanisms of kidney uptake of radiolabeled peptides. J Nucl Med. 2007;48:596–601.

Rolleman EJ, Valkema R, De JM, Kooij PP, Krenning EP. Safe and effective inhibition of renal uptake of radiolabelled octreotide by a combination of lysine and arginine. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2003;30:9–15.

de Jong M, Rolleman EJ, Bernard BF, et al. Inhibition of renal uptake of indium-111-DTPA-octreotide in vivo. J Nucl Med. 1996;37:1388–92.

Thelle K, Christensen EI, Vorum H, Orskov H, Birn H. Characterization of proteinuria and tubular protein uptake in a new model of oral L-lysine administration in rats. Kidney Int. 2006;69:1333–40.

Pimm MV, Gribben SJ. Prevention of renal tubule re-absorption of radiometal (indium-111) labelled Fab fragment of a monoclonal antibody in mice by systemic administration of lysine. Eur J Nucl Med. 1994;21:663–5.

Behr TM, Goldenberg DM, Becker W. Reducing the renal uptake of radiolabeled antibody fragments and peptides for diagnosis and therapy: present status, future prospects and limitations. Eur J Nucl Med. 1998;25:201–12.

Bernard BF, Krenning EP, Breeman WA, et al. D-lysine reduction of indium-111 octreotide and yttrium-90 octreotide renal uptake. J Nucl Med. 1997;38:1929–33.

van Eerd JE, Vegt E, Wetzels JF, et al. Gelatin-based plasma expander effectively reduces renal uptake of 111In-octreotide in mice and rats. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:528–33.

Vegt E, Wetzels JF, Russel FG, et al. Renal uptake of radiolabeled octreotide in human subjects is efficiently inhibited by succinylated gelatin. J Nucl Med. 2006;47:432–6.

Rolleman EJ, Bernard BF, Breeman WA, et al. Molecular imaging of reduced renal uptake of radiolabelled [DOTA0, Tyr3]octreotate by the combination of lysine and Gelofusine in rats. Nuklearmedizin. 2008;47:110–5.

Gekle M. Renal tubule albumin transport. Annu Rev Physiol. 2005;67:573–94.

Rose B, Post T. Clinical physiology of acid-base and electrolyte disorders. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001.

Polgár L. Structure and function of serine proteases. In: Neuberger A, Brocklehurst K, editors. New comprehensive biochemistry. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 1987. p. 159–200.

Skopp RN, Lane LC. Fingerprinting of proteins cleaved in solution by cyanogen bromide. Appl Theor Electrophor. 1988;1:61–4.

Hnatowich DJ, Childs RL, Lanteigne D, Najafi A. The preparation of DTPA-coupled antibodies radiolabeled with metallic radionuclides: an improved method. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65:147–57.

Le Panse S, Verroust P, Christensen EI. Internalization and recycling of glycoprotein 280 in BN/MSV yolk sac epithelial cells: a model system of relevance to receptor-mediated endocytosis in the renal proximal tubule. Exp Nephrol. 1997;5:375–83.

Gburek J, Verroust PJ, Willnow TE, et al. Megalin and cubilin are endocytic receptors involved in renal clearance of hemoglobin. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2002;13:423–30.

Behe M, Kluge G, Becker W, Gotthardt M, Behr TM. Use of polyglutamic acids to reduce uptake of radiometal-labeled minigastrin in the kidneys. J Nucl Med. 2005;46:1012–5.

Trejtnar F, Laznicek M, Laznickova A, et al. Biodistribution and elimination characteristics of two 111In-labeled CCK-2/gastrin receptor-specific peptides in rats. Anticancer Res. 2007;27:907–12.

Gotthardt M, Fischer M, Naeher I, et al. Use of the incretin hormone glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) for the detection of insulinomas: initial experimental results. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2002;29:597–606.

Barone R, Van der SP, Devuyst O, et al. Endocytosis of the somatostatin analogue, octreotide, by the proximal tubule-derived opossum kidney (OK) cell line. Kidney Int. 2005;67:969–76.

O'Carroll AM. Localization of messenger ribonucleic acids for somatostatin receptor subtypes (sstr1–5) in the rat adrenal gland. J Histochem Cytochem. 2003;51:55–60.

Reubi JC, Schar JC, Waser B, et al. Affinity profiles for human somatostatin receptor subtypes SST1-SST5 of somatostatin radiotracers selected for scintigraphic and radiotherapeutic use. Eur J Nucl Med. 2000;27:273–82.

Ludvigsen E, Olsson R, Stridsberg M, Janson ET, Sandler S. Expression and distribution of somatostatin receptor subtypes in the pancreatic islets of mice and rats. J Histochem Cytochem. 2004;52:391–400.

Krempels K, Hunyady B, O'Carroll AM, Mezey E. Distribution of somatostatin receptor messenger RNAs in the rat gastrointestinal tract. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1948–60.

Le Romancer M, Cherifi Y, Levasseur S, et al. Messenger RNA expression of somatostatin receptor subtypes in human and rat gastric mucosae. Life Sci. 1996;58:1091–8.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Bianca Lemmers-van de Weem, Kitty Lemmens-Hermans, Lieke Joosten, Gabie de Jong, Gerben Franssen and Rafke Schoffelen for their invaluable help in the animal experiments.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Vegt, E., Eek, A., Oyen, W.J.G. et al. Albumin-derived peptides efficiently reduce renal uptake of radiolabelled peptides. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 37, 226–234 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-009-1239-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-009-1239-1