Abstract

Introduction

Rising life-expectancy in the modern society has resulted in a rapidly growing prevalence of dementia, particularly of Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Dementia turns into one of the most common age-related disorders with deleterious consequences for the concerned patients and their relatives, as well as worrying effects on the socio-economic systems. These facts justify strengthened scientific efforts to identify the pathologic origin of dementing disorders, to improve diagnosis, and to interfere therapeutically with the disease progression.

Basic pathologies

In the recent years, remarkable progress has been made concerning the identification of molecular mechanisms underlying the pathology of neurodegenerative disorders. Growing evidence indicates that a common basis of many neurodegenerative dementias can be found in increased production, misfolding and pathological aggregation of proteins, such as ß-amyloid, tau protein, a-synuclein, or the recently described ubiquitinated TDP-43. This progressive insight in pathological processes is paralleled by the development of new therapeutic approaches. However, the exact contribution or mechanism of different pathologies with regard to the development of disease is not yet sufficiently clear. Considerable overlap of pathologies has been documented in different types of clinically defined dementias post mortem, and it has been difficult to correlate post mortem histopathology data with disease-expression during life. Molecular imaging procedures may play a valuable role to circumvent this limitation.

Relevance for imaging studies

In general, methods of molecular imaging have recently experienced an impressive advance, with numerous new and improved technologies emerging. These exciting tools may play a key role in the future regarding the evaluation of pathomechanisms, preclinical evaluation of new diagnostic procedures in animal models, selection of patients for clinical trials, and therapy monitoring. In this overview, molecular key pathologies, which are currently regarded to be strongly associated with the development of different dementias, will be shortly summarized; it will also be discussed how state-of-the-art imaging technology can assist to visualize these processes now and in the future.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Hebert LE, Scherr PA, Bienias JL, Bennett DA, Evans DA. Alzheimer disease in the US population: prevalence estimates using the 2000 census. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:1119–22.

Neumann M, Sampathu DM, Kwong LK, et al. Ubiquitinated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science. 2006;314:130–3.

Pearson HA, Peers C. Physiological roles for amyloid beta peptides. J Physiol. 2006;575:5–10.

Dickson TC, Vickers JC. The morphological phenotype of beta-amyloid plaques and associated neuritic changes in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroscience. 2001;105:99–107.

Armstrong RA. Beta-amyloid plaques: stages in life history or independent origin. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 1998;9:227–38.

Knopman DS, Parisi JE, Salviati A, et al. Neuropathology of cognitively normal elderly. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2003;62:1087–95.

Van Broeck B, Van Broeckhoven C, Kumar-Singh S. Current insights into molecular mechanisms of Alzheimer disease and their implications for therapeutic approaches. Neurodegener Dis. 2007;4:349–65.

Yan Y, Wang C. Abeta40 protects non-toxic Abeta42 monomer from aggregation. J Mol Biol. 2007;369:909–16.

Kim J, Onstead L, Randle S, et al. Abeta40 inhibits amyloid deposition in vivo. J Neurosci. 2007;27:627–33.

Shen J, Kelleher RJ 3rd. The presenilin hypothesis of Alzheimer’s disease: evidence for a loss-of-function pathogenic mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:403–9.

Kumar-Singh S, Van Broeckhoven C. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: current concepts in the light of recent advances. Brain Pathol. 2007;17:104–14.

Zaccai J, McCracken C, Brayne C. A systematic review of prevalence and incidence studies of dementia with Lewy bodies. Age Ageing. 2005;34:561–6.

Forster E, Lewy FH. Paralysis agitans. In: Lewandowsky M, editor. Pathologische Anatomie. Handbuch der Neurologie. Berlin: Springer Verlag; 1912. pp. 920–33.

Chandra S, Gallardo G, Fernandez-Chacon R, Schluter OM, Sudhof TC. Alpha-synuclein cooperates with CSPalpha in preventing neurodegeneration. Cell. 2005;123:383–96.

Tofaris GK, Spillantini MG. Physiological and pathological properties of alpha-synuclein. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2007;64:2194–201.

Goedert M. Alpha-synuclein and neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2001;2:492–501.

Weisman D, Cho M, Taylor C, Adame A, Thal LJ, Hansen LA. In dementia with Lewy bodies, Braak stage determines phenotype, not Lewy body distribution. Neurology. 2007;69:356–9.

Iseki E. Dementia with Lewy bodies: reclassification of pathological subtypes and boundary with Parkinson's disease or Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropathology. 2004;24:72–8.

Neary D, Snowden JS, Gustafson L, et al. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology. 1998;51:1546–54.

Ikeda M, Ishikawa T, Tanabe H. Epidemiology of frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2004;17:265–8.

Snowden JS. Semantic dysfunction in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 1999;10(Suppl 1):33–6.

Johnson JK, Diehl J, Mendez MF, et al. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: demographic characteristics of 353 patients. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:925–30.

Zhang YJ, Xu YF, Dickey CA, et al. Progranulin mediates caspase-dependent cleavage of TAR DNA binding protein-43. J Neurosci. 2007;27:10530–4.

Amador-Ortiz C, Lin WL, Ahmed Z, et al. TDP-43 immunoreactivity in hippocampal sclerosis and Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 2007;61:435–45.

Davies RR, Hodges JR, Kril JJ, Patterson K, Halliday GM, Xuereb JH. The pathological basis of semantic dementia. Brain. 2005;128:1984–95.

Garrard P, Hodges JR. Semantic dementia: clinical, radiological and pathological perspectives. J Neurol. 2000;247:409–22.

Shi J, Shaw CL, Du Plessis D, et al. Histopathological changes underlying frontotemporal lobar degeneration with clinicopathological correlation. Acta Neuropathol (Berl). 2005;110:501–12.

Cairns NJ, Bigio EH, Mackenzie IR, et al. Neuropathologic diagnostic and nosologic criteria for frontotemporal lobar degeneration: consensus of the Consortium for Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration. Acta Neuropathol (Berl). 2007;114:5–22.

McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34:939–44.

Godbolt AK, Josephs KA, Revesz T, et al. Sporadic and familial dementia with ubiquitin-positive tau-negative inclusions: clinical features of one histopathological abnormality underlying frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:1097–101.

Shoghi-Jadid K, Small GW, Agdeppa ED, et al. Localization of neurofibrillary tangles and beta-amyloid plaques in the brains of living patients with Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;10:24–35.

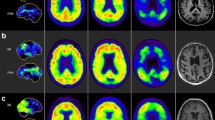

Klunk WE, Engler H, Nordberg A, et al. Imaging brain amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease with Pittsburgh Compound-B. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:306–19.

Verhoeff NP, Wilson AA, Takeshita S, et al. In-vivo imaging of Alzheimer disease beta-amyloid with [11C]SB-13 PET. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004;12:584–95.

Nordberg A. PET imaging of amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol. 2004;3:519–27.

Rowe CC, Ng S, Ackermann U, et al. Imaging beta-amyloid burden in aging and dementia. Neurology. 2007;68:1718–25.

Engler H, Forsberg A, Almkvist O, et al. Two-year follow-up of amyloid deposition in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2006.

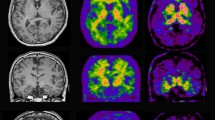

Drzezga A, Grimmer T, Henriksen G, et al. Imaging of amyloid plaques and cerebral glucose metabolism in semantic dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroimage. 2008;39:619–33.

Price JL, Morris JC. Tangles and plaques in nondemented aging and “preclinical” Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 1999;45:358–68.

Forsberg A, Engler H, Almkvist O, et al. PET imaging of amyloid deposition in patients with mild cognitive impairment. Neurobiol Aging. 2007.

Kemppainen NM, Aalto S, Wilson IA, et al. PET amyloid ligand [11C]PIB uptake is increased in mild cognitive impairment. Neurology. 2007;68:1603–6.

Citron M. Strategies for disease modification in Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:677–85.

Klunk WE, Wang Y, Huang GF, et al. The binding of 2-(4′-methylaminophenyl)benzothiazole to postmortem brain homogenates is dominated by the amyloid component. J Neurosci. 2003;23:2086–92.

Lockhart A, Lamb JR, Osredkar T, et al. PIB is a non-specific imaging marker of amyloid-beta (Abeta) peptide-related cerebral amyloidosis. Brain. 2007;130:2607–15.

Engler H, Santillo AF, Wang SX, et al. In vivo amyloid imaging with PET in frontotemporal dementia. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2007.

Agdeppa ED, Kepe V, Liu J, et al. Binding characteristics of radiofluorinated 6-dialkylamino-2-naphthylethylidene derivatives as positron emission tomography imaging probes for beta-amyloid plaques in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2001;21:RC189.

Fodero-Tavoletti MT, Smith DP, McLean CA, et al. In vitro characterization of Pittsburgh compound-B binding to Lewy bodies. J Neurosci. 2007;27:10365–71.

Johansson A, Savitcheva I, Forsberg A, et al. [(11)C]-PIB imaging in patients with Parkinson's disease: Preliminary results. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2007.

Bacskai BJ, Frosch MP, Freeman SH, et al. Molecular imaging with Pittsburgh Compound B confirmed at autopsy: a case report. Arch Neurol. 2007;64:431–4.

Skoch J, Dunn A, Hyman BT, Bacskai BJ. Development of an optical approach for noninvasive imaging of Alzheimer’s disease pathology. J Biomed Opt. 2005;10:11007.

Skoch J, Hyman BT, Bacskai BJ. Preclinical characterization of amyloid imaging probes with multiphoton microscopy. J Alzheimers Dis. 2006;9:401–7.

Jack CR Jr., Marjanska M, Wengenack TM, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of Alzheimer’s pathology in the brains of living transgenic mice: a new tool in Alzheimer’s disease research. Neuroscientist. 2007;13:38–48.

Manook A, Henriksen G, Platzer S, et al. Feasibility of in vivo amyloid plaque imaging in a transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. J Nucl Med. 2007;48(Supplement 2):116P.

Maeda J, Ji B, Irie T, et al. Longitudinal, quantitative assessment of amyloid, neuroinflammation, and anti-amyloid treatment in a living mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease enabled by positron emission tomography. J Neurosci. 2007;27:10957–68.

Huhne R, Koch FT, Suhnel J. A comparative view at comprehensive information resources on three-dimensional structures of biological macro-molecules. Brief Funct Genomic Proteomic. 2007.

Reichert J, Suhnel J. The IMB Jena Image Library of Biological Macromolecules: 2002 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:253–4.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Dr. Manuela Neumann (Center for Neuropathology and Prion Research, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, Munich, Germany) for her careful revision of the manuscript and most valuable advice, Prof. Dr. Jürgen Schlegel (Insititute for Pathology, Technische Universtiät München, Munich, Germany) for supply of the histopathological sections and highly appreciated comments, and Dr. Jürgen Sühnel (Biocomputing Group, Leibniz Institute for Age Research–Fritz Lipmann Institute) for supply of the protein figures. Special thanks also to Brian Les Houches (VINS, Amsterdam–Munich) for valuable suggestions.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that they have no relevant financial or any other interests in this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Drzezga, A. Basic pathologies of neurodegenerative dementias and their relevance for state-of-the-art molecular imaging studies. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 35 (Suppl 1), 4–11 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-007-0697-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00259-007-0697-6