Abstract

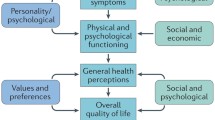

The CAST was a randomized, double-blind placebo-controlled multicentre trial of antiarrhythmic medications designed to suppress ventricular arrhythmias in patients after an acute myocardial infarction (MI). A collection of 21 items derived from established scales was used to assess aspects of quality of life in CAST. The questions focused on symptoms, mental health, physical functioning, social functioning, life satisfaction, and life expectancy. Additional aspects included exposure to major stressful life events, and perceived social support and social integration. Work status was also recorded. Using the baseline values of 1465 (98%) out of 1498 patients enrolled in the CAST main study between 15 June 1987 and 19 April 1989, the reliability and validity of the scales used in CAST were computed. High internal consistency reliability (≥0.70) was found for Symptoms, Mental Health, and Physical Functioning. The discriminative validity, in particular for Symptoms, Mental Health, Physical and Social Functioning, showed that patients with heart failure and previous MI, as well as those suffering from angina and dyspnea, had a worse quality of life than those patients who were not experiencing these symptoms. It was concluded that the scales selected to form the CAST quality of life questionnaire were both reliable and clinically valid for this patient population and therefore could be used to detect disease progression and treatment effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Kennedy GJ, Hofer MA, Cohen D, et al. Significance of depression and cognitive impairment in patients undergoing programmed stimulation of cardiac arrhythmias.Psychosom Med 1987;49: 410–421.

Carney RM, Rich MW, Freedland KE, et al. Major depressive disorder predicts cardiac events in patients with coronary artery disease.Psychosom Med 1988;50: 627–633.

Wiklund I, Odén A, Sanne H, et al. Prognostic importance of somatic and psychosocial variables after a first myocardial infarction.Am J Epidemiol 1988;128: 786–795.

Ahern DK, Gorkin L, Anderson JL, et al. Biobehavioral variables and mortality or cardiac arrest in the Cardiac Arrhythmia Pilot Study (CAPS).Am J Cardiol 1990;66: 59–62.

Palmore E, Luikhardt C. Health and social factors related to life satisfaction.J Health Soc Behav 1972;13: 68–80.

Wenger NK, Mattson ME, Furberg CD, et al. Assessment of quality of life in clinical trials of cardiovascular therapies.Am J Cardiol 1984;54: 908–913.

Spitzer WO. State of science 1986: quality of life and functional status as target variables for research.J Chronic Dis 1987;40: 465–471.

Franciosa JA, Park M, Levine TB. Lack of correlation between exercise capacity and indexes of resting left ventricular performance in heart failure.Am J Cardiol 1981;47: 33–39.

Guyatt GH. Methodological problems in clinical trials in heart failure.J Chron Dis 1985;38: 353–363.

McSweeny AJ, Grant I, Heaton RK, et al. Life quality of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.Arch Intern Med 1982;142: 473–478.

Wiklund I, Comerford MB, Dimenäs E. The relationship between exercise tolerance and quality of life in angina pectoris.Clin Cardiol 1991;14: 204–208.

Cornett SJ, Watson JE.Cardiac Rehabilitation. An Interdisciplinary Team Approach. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1984.

The CAST Investigators. The Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial (CAST).New Engl J Med 1989;321: 386–338.

Soyka LF. Safety considerations and dosing guidelines for encainide in supraventricular arrhythmias.Am J Cardiol 1988;62: 63L-68L.

Gentzkow GD, Sullivan JY. Extracardiac adverse effects of flecainide.Am J Cardiol 1984;53: 101B-105B.

Gorkin L, Schron EB, Ahern DK,et al. Emotional status and antiarrhythmic medications in the Cardiac Arrhythmia Pilot Study (CAPS). Unpublished, Providence RI.

Stewart AL, Greenfield S, Hays RD, et al. Functional status and well-being of patients with chronic conditions. Results from the Medical Outcomes Study.J Am Med Assoc 1989;262: 907–913.

Rogers WJ for the SOLVD Investigators. Functional status of 2569 patients with symptomatic congestive heart failure randomized between enalapril and placebo in the studies of left ventricular dysfunction.Circulation 1991;84(S II): 11–311.

Ruberman W, Weinblatt E, Goldberg JD, et al. Psychosocial influences on mortality after myocardial infarction.N Engl J Med 1984;311: 552–559.

Wiklund I, Lindvall K, Swedberg K, et al. Self-assessment of quality of life in severe heart failure. An instrument for clinical use.Scand J Psychol 1987;28: 220–225.

Berkman LF, Syme SL. Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: A nine-year follow-up study of Alameda County residents.Am J Epidemiol 1979;109: 186–204.

House JS, Robbins C, Metzner HL. The association of social relationships and activities with mortality: Prospective evidence from the Tecumseh Community Health Study.Am J Epidemiol 1982;116: 123–140.

Andrews FM, Withey SB. Developing measures of perceived life quality: Results from several national surveys.Social Indicators Research 1974;1: 1.

Carmines EG, Zeller RA. Reliability and validity assessment. In: Sullivan JL, Niemi RG, eds.Quantitative Applications in Social Sciences. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications, 1983.

Guyatt G, Bombardier C, Tugwell PX. Measuring disease-specific quality of life in clinical trials.Can Med Assoc J 1986;134: 889–895.

Kirshner B, Guyatt G. A methodologic framework for assessing health indices.J Chronic Dis 1985;38: 27–36.

Cronbach LJ. Co-efficient alpha in the internal structure of tests.Psychometrika 1951;16: 297–334.

Dixon WJ.BMDP Statistical Software Manual. Berkely: University of California Press, 1990.

Gorkin L, Norvell NK, Rosen RC,et al. Assessment of quality of life in patients with left ventricular dysfunction as observed from the baseline data of the Studies of Left Ventricular Dysfunction (SOLVD) trial. Submitted.

Ware JE. Methodological considerations in the selection of health status assessment procedures. In: Wenger NK, Mattson ME, Furberg CD, Elinson J, eds.Assessment of Quality of Life in Clinical Trials of Cardiovascular Therapies. USA: LE Jacq Publ Inc 1984: pp. 87–111.

Willens HJ, Blevins RD, Wrisley D, et al. The prognostic value of functional capacity in patients with mild to moderate heart failure.Am Heart J 1987;114: 377–382.

Wiklund I, Herlitz J, Hjalmarson Å. Quality of life five years after myocardial infarction.Eur Heart J 1989;10: 464–472.

Trelawny-Ross C, Russell O. Social and psychological responses to myocardial infarction: Multiple determinants of outcome at six months.J Psychosom Res 1987;31: 125–130.

Goldman L, Hashimoto B, Cook EF, et al. Comparative reproducibility and validity of systems for assessing cardiovascular functional class: advantages of a new specific activity scale.Circulation 1981;64: 1227–1234.

Feinstein AR, Fisher MB, Pigeon JG. Changes in dyspnea fatigue ratings as indicators of quality of life in the treatment of congestive heart failure.Am J Cardiol 1989;64: 50–55.

Gorkin L, Schron E, Wiklund I,et al. for the CAST Investigators. Psychosocial predictors of mortality in the Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial (CAST)Am J Cardiol, in press.

Guyatt G, Van Zanten S, Feeny D, et al. Measuring quality of life in clinical trials: taxonomy and review.Can Med Assoc J 1989;140: 1441–1448.

Wiklund I, Dimenäs E, Wahl M. Factors of importance when evaluating quality of life in clinical trials.Controlled Clin Trials 1990;11: 169–179.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Wiklund, I., Gorkin, L., Pawitan, Y. et al. Methods for assessing quality of life in the Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial (CAST). Qual Life Res 1, 187–201 (1992). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00635618

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00635618